The food universe operates in unusual ways and I’ve learned to simply go with the flow. In October 2015, I went to Vietnam with my travel buddy and stylist Karen Shinto. My chief aim was to do a little more research about pho. I’d traveled to Vietnam many times since 2003 and on one occasion, reported a pho story for Saveur magazine. This time I was circling back to check in with the pho scene with more depth.

Flying from Phu Quoc island to Hanoi, we were seated next to a young woman who introduced herself and asked if I was from America, what we were up to in Vietnam. Amy Do had overheard my conversation with Karen. She was friendly in an unusual, refreshing way. She was in the hospitality industry and was looking to network. I liked her boldness.

Amy was an orphan raised by a foster mother and explained that since she lacked blood relatives to take care of her, she learned to be more outgoing. Her English was honed by striking up conversations with strangers. Soon we were speaking in Viet-glish. At the end of the two-hour flight, we’d exchanged cell numbers and made a date for the next day: Amy’s foster mother would show Karen and me how she made pho! (To a researcher and writer like me, that kind of invitation is gold.)

The next morning, we taxied over to a Bo Nhung Dam 46, a beef hot pot restaurant, co-owned by Äá»— Trá»ng Quang, who was married to one of Amy’s foster sisters. Quang welcomed us into the kitchen where there was prep going on for the beef hot pot. It was such a treat to be invited into the back of a Vietnamese restaurant kitchen. Amy and her family were totally open and supportive of my mission to write The Pho Cookbook.

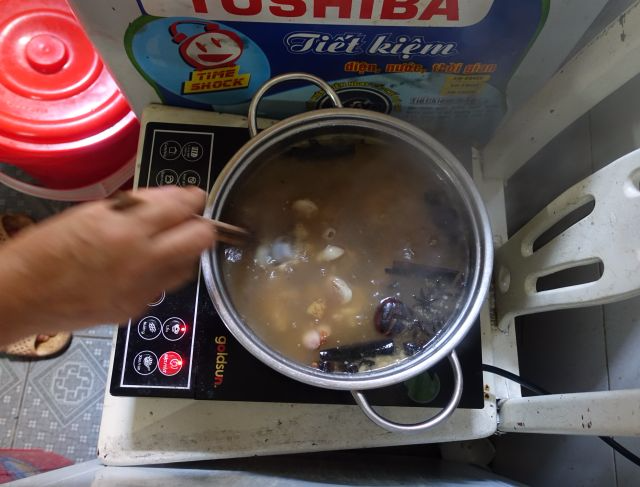

In one corner, Amy’s foster mother began showing us her approach to making pho. The kitchen’s wok station used propane tanks. Other cooking, such as simmering the broth for the hot pot, was done using a giant rice cooker. The restaurant employed electric portable burners on the dining tables to keep the hot pots warm for guests; butane-fueled burners were inefficient, Quang said. It was natural that they’d use the electric burners in the kitchen, too. I never thought that a glass top portable burner would be used for toasting spices, ginger, and shallot. Viet cooks make due.

Beef bones are pricey in Vietnam so cooks often blend pork and beef together in pho broth. That was the case with Amy’s mom too. In the pot below, the pork bones are easily identified by their smaller size.

She then seasoned the broth with a “pho seasoning†packet and assembled the bowl at the top of this post. That little lime is not too tart. On the side is a pile of salt, pepper, and MSG – a blend that I saw at several restaurants in Hanoi.

The beef used for the topping was meticulously trimmed shank. The sinews had been removed by hand. Yes, that kind of work is being done daily in Vietnam. It was a delicate bowl and made with much warmth and grace.

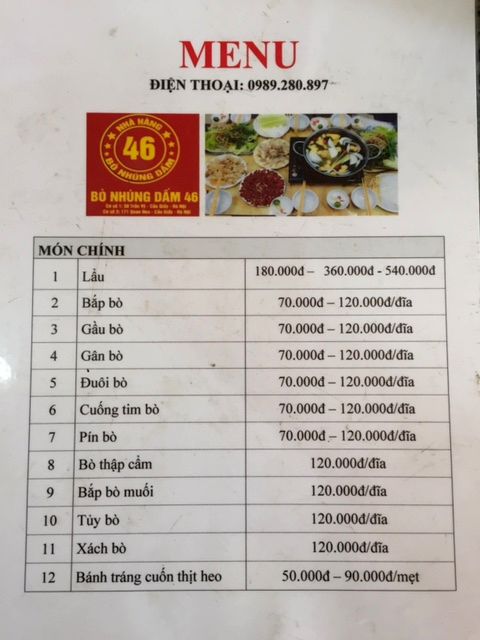

But admittedly, the specialty of the house was the beef hot pot, which Quang presented to Karen and me in its full glory. Among the things we ate were brisket, artery, thinly sliced penis, tail, pork shank, pork belly, and marrow. It was wonderful, the morsels lightly cooked in the light broth then wrapped in paper thin Hanoi-style rice paper, lettuce, and herbs. Quang’s sauce featured pineapple, pork broth, and mam nem (a sludgy, funky southern-style fermented fish sauce) was deliciously balanced.

The family and staff at Bo Nhung Dam 46 do not speak much English but Quang said that it’s easy to order: Get the basic hot pot and then add other proteins a la carte. He said that even Vietnamese people can get a little confused so he created his menu to be simple to navigate. Prices are according to size and per plate. Hints: Number 1 is the basic hot pot. Number 8 is a bit of everything.

When there was a lull in the action, I sat down with Quang to chat about his personal connection to food. Quang was actively engaged in the kitchen, cooking and managing things. He explained that he’d grown up watching his mom and aunties cook. He absorbed his knowledge by observation and then practiced and tinkered.

He also loved to eat and his side job as a taxi driver enabled him to know lots of good spots in town; everyone in Vietnam seems to have multiple gigs. Quang owned the restaurant with his brothers, an accountant and policeman. They shared in the responsibilities and profits.

What was his pho experience like? Quang, 39, explained that he wasn’t born and raised in Hanoi. Pho was not available in his village. He didn’t taste pho until he came to the capital in 1986, when he was ten years old and the trip from the countryside involved cyclo and boat rides. He was excited to venture to the city.

“I never forgot how the Hanoi pho vendor hand cut the noodles and meat,†he said, making delicate motions with his hand. “The broth was spectacular.â€

I was born in Saigon and had single-handedly polished off an entire bowl when I was five. I took it for granted. Pho may be the national food of Vietnam, but it’s not a national birthright. It’s a special food that people appreciate, cultivate, and share.

They say you’re not supposed to talk to strangers but I’m sure glad to have met Amy and her family. They added to The Pho Cookbook in ways that I never could have expected.

Related post:

- Finding Good Hanoi Street Food Means Eating with Ladies Who Lunch

- MSG in Pho and What to Do about It

2/2/17 Pho Cookbook update! My publisher just informed me that Amazon editors picked The Pho Cookbook for their February 2017 list of best books. Selection is based on what Amazon editors consider to be keepers, best sellers, and favorites. Thanks so much for supporting the book and my work. And we're 5 days away from release. Wow. See what else is included here.