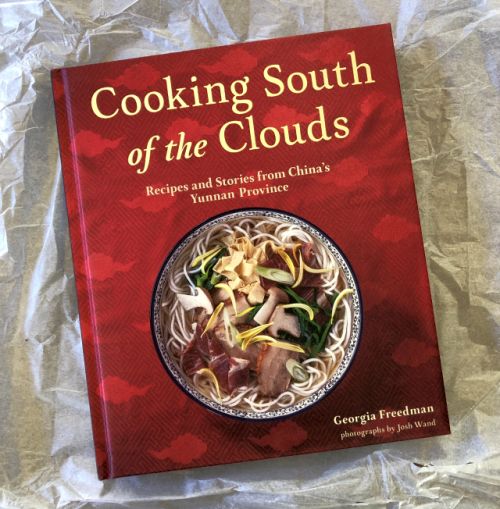

I’ve long contended that China influenced Vietnamese pho big time, but it wasn’t till this week that I got a clear sense of what Chinese beef pho is actually like. Yes, it exists, and I found a recipe in my friend Georgia Freedman’s new book, Cooking South of the Clouds, which focuses on the cooking of Yunnan province located in southwestern China. In Mandarin, Yunnan means south of the clouds. The Chinese know Vietnam as Yuenan, which means far (or further) south. Vietnam was part of China for a total of 1,000 years so it has figured into being part of the Chinese kingdom.

Long ago, when I was studying Chinese language and culture, I sensed there were many ties between Yunnan and Yuenan. Aside from the similar names in Mandarin, the Red River (Song Hong in Vietnamese) flows from Yunnan into northern Vietnam and empties into the Gulf of Tonkin. Ideas and trade have been flowing on the river and across the porous border to connect the people of the two areas.

No wonder the history of pho has a lot to do with Chinese street food vendors who were peddling noodle soup in and around Hanoi. They were among the first pho cooks on Vietnamese soil!

I’ve only been to Yunnan once, in 1992 for about a week, so it wasn’t much of a learning experience or discovery of cultural and culinary linkages. For that reason, I’ve been supportive and interested in Georgia’s efforts to illuminate Yunnan cooking. It took many years for her and her husband, Josh, who took the photographs, to finish the book and get it published. If you’re into regional Chinese cooking, Cooking South of the Clouds is worth getting for your library and to cook from.

Chinese beef pho vs. Viet beef pho

When I studied Georgia’s recipe for beef noodle soup, which she says is the same as Vietnamese pho prepared downstream, I noticed these similarities between Yunnan and Hanoi-style pho: the use of black cardamom, star anise and fennel (see my Pho Spice Blend for more info); and the preference for mint, minced ginger, and fresh garlic. Hardcore pho lovers in northern Vietnam use mint (not Thai basil) to garnish pho with herbal freshness. A bit of ginger adds fragrance, too. And the garlic is nowadays represented in a vinegary condiment that you can find at many pho shops in Hanoi; a simple recipe for giam toi is in The Pho Cookbook and here on this site.

The Chinese beef pho broth has no shallot, ginger or fish sauce. As a result, it’s very subtle and light in flavor, especially with the use of beef shank, which imparts collagen but it isn’t a beefy-tasting cut. The last-minute additions of umami-laden mustard greens, chile oil, Sichuan peppercorn, garlic chives, and vinegar are totally Chinese.

Wondering what the recipe’s end result would be like, I made a batch of Chinese beef pho but instead of simmering the broth in a pot for hours on the stove, I used my Fagor Lux multicooker (it’s the same as an Instant Pot but the Fagor has a fabulous nonstick ceramic coated inner pot that heats up hot and cleans up like a dream). I adore using a pressure cooker or electric multicooker for pho experiments.

Do you have to have all the toppings?

The rest of the work was pulling things from the fridge -- I had the Fermented Chinese Mustard Greens from a couple weeks back and (bonus!) it already had pickled chiles and garlic so I chopped those up as a topping. In my pantry was homemade chile oil. There was mint in the garden, and some garlic chives too. I also had the garlic vinegar in the fridge and found that that had more impact on the soup than the garlic chive. And Sichuan peppercorn is part of my spice collection.

You don’t have to have all the things that Georgia lists (she says they’re optional), but I’d suggest 4 or 5 items to add oomph to your Chinese beef pho bowl. The broth is very delicately flavored so it needs something. At the least, have some soy sauce and vinegar.

How was the flavor?

It wasn’t Vietnamese pho. It tasted like Chinese food but of Yunnan. The multitude of additions reminded me of Yunnan’s signature dish, Crossing the Bridge Rice Noodles, a complicated noodle soup with a zillion different toppings; the broth features pork, chicken, star anise and black cardamom, and is seasoned with soy sauce.

Most Chinese beef dishes are not super beefy, which is perhaps why the broth for the Chinese pho is so light. The Vietnamese, on the other hand, adore the hearty, fatty, rich flavors of beef brisket and the like. We also adore our fish sauce and charring the shallot/onion and ginger.

I tried adding fish sauce to the broth but it didn’t make things more Viet-ish. The Chinese pho was better off with soy sauce and the other add-ins because as Georgia writes in the Cooking South of the Clouds, the topping options “give it a local twist.”

So yes, you can be neighbors and perhaps even kin, but you don’t have to cook pho the same.

Yunnan Beef Pho Noodle Soup

Prep

Cook

Inactive

Total

Yield 4 serving

In Georgia Freedman's book, Cooking South of the Clouds, she titles this recipe as "Beef Noodle Soup" -- its translation from Chinese characters. In the recipe introduction, she refers to it as being "exactly the same soup that is called pho just a few miles down south, in Vietnam." For that reason, I've decided to add "Yunnan pho" to the title to give it more of a spotlight. If you don't have Sichuan peppercorn, use black pepper like the Viets do! For information on the spices, see the Pho Spice Blend.

Ingredients

- 2 pounds cross-cut beef shank, including marrow bones

- 1 ½ pounds beef leg bones, such as knuckle bones

- 2 Chinese black cardamom pods, cracked open with a meat mallet

- 2 star anise (16 robust points total)

- 1 teaspoon fennel seed

- 1 tablespoon fine sea salt

- 4 large handfuls fresh rice noodles or 12 ounces dried flat rice noodles, such as pad thai or banh pho

- 6 to 12 ounces raw beef steak, such as sirloin or culotte, sliced very thinly (use maximum if not using cooked shank in bowls)

Topping options

- 1 bunch of fresh mint

- 1 handful garlic (Chinese) chives, blanched, rinsed in cold water, and cut into 1-inch pieces

- 4 slender green onions, white and green parts, thinly sliced

- Minced garlic mixed with water to cover by ½ inch, or Pho Garlic Vinegar

- 2 tablespoons minced peeled ginger

- 1 cup chopped Fermented Chinese Mustard Greens (include some of the chile and garlic, for extra punch)

- Soy sauce

- Zhenjiang vinegar or 2:1 blend of balsamic and apple cider vinegar

- Dried chile flakes

- Homemade Chile Oil

- Ground toasted Sichuan Peppercorn

- Pickled chiles

Instructions

- To cook the broth in a 6-quart pressure cooker, put the beef shanks, bones, cardamom, star anise, and fennel in the pot, then add 7 ¼ cups water (use 8 cups water for a multicooker such as a Fagor Lux or Instant Pot). Lock on the lid and bring to high pressure. As needed, adjust the heat to maintain pressure. Let cook on high pressure for 20 minutes, then turn off the heat (or unplug the multicooker). Let naturally depressurize for 15 minutes on a cool burner (allow a multicooker to depressurize for 20 minutes), then release residual pressure. (When cooking in a regular large pot, bring the shank, bones and 12 cups water to a boil. Skim any foam on the surface, before adding the spices. Adjust the heat to simmer for 3 to 4 hours.)

- Regardless of method, when the broth is done, remove the shank from the pot and let sit in a bowl of water for 10 minutes to cool, then strain and let the meat cool. Strain the broth through a fine mesh strainer or better yet, line the strainer with muslin for super clear broth! Remove as much fat as you like, then add the salt. You should net about 8 cups of broth; if needed, boil the broth to concentrate the flavor or add water to dilute. (The beef and broth can be refrigerated up to 4 days before using.)

- If using the cooked beef, thinly slice the meat across the grain and set aside. In a large pot of boiling water, cook the noodles until soft and chewy, then drain and divide between four noodle soup bowls. Arrange the sliced cook beef and steak on top.

- Bring the broth a boil and ladle about 2 cups of broth into each bowl. Serve with the topping options at the table.

Notes

Adapted from Georgia Freedman’s Cooking South of the Clouds (Kyle Books, 2018)

Courses main dish

Cuisine Chinese

Joanne says

I am using an instant pot and you mentioned to put 2 cups of water into the instant pot. how do i end up with 8 cups of broth? should i add more water after it's done in the instant pot?

Andrea Nguyen says

I'm so sorry for that mistake!!! Yikes. I just corrected it. It's 7 1/4 cups water in the IP.

Toàn says

Thanks for the savory article. One thing I would find offense is the statement that somehow Vietnam was part of China for a 1000 years. This is facutally and culturally worng. Yes, China has tried to swallow Vietnam and occupied its land on and off for about 1000 years. It has always failed in the end. Check your history. Even on a remotely objective lingusitic level, the Viet people share an Austro-Asiatic root, far from the Sino-Tibetant Chinese tongue. This is why attempts to use Chinese or even Nôm quickly gave in to the Latin based phonetic system.

Andrea Nguyen says

Historians consider the on-an-off relationship between China and Vietnam to be a situation of Chinese domination and colonization. Many Viet people take offense to this because Viet people are fiercely independent. It is fine to perceive things differently but a fair amount Vietnamese culture has Chinese roots.

This article is about the way people exchange ideas without borders. There's no need to put up borders when it comes to cuisine. My statement comes from academic information and research done in books. Here's an online reference from Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_domination_of_Vietnam

With regard to Vietnamese language, the southern Chinese language also share Austroasiatic roots, as discussed here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vietnamese_language

People have moved across borders for eons and thank goodness we're in a situation now when Vietnam enjoys self-determination.

Linh Nguyen says

Just a comment. Please don't use Wikipedia as reference, you definitely knew that Wikipedia is written by whoever have interest to write.

Andrea Nguyen says

I regularly cross-reference with printed works.

Marie says

This is not "factually wrong". This is the reality of what happened. While the Vietnamese people existed before Chinese rule, they were not a polity. Vietnamese is an Austroasiatic language but the morphology highly resembles Chinese (particularly Cantonese due to similar substrates from Kra-Dai people). Khmer is another Austroasiatic language with foreign influence but it is nowhere near as linguistically shifted from its roots as Vietnamese is. The Vietnamese are a Southeast Asian people but their genetics now lie in between Southeast and Northeast Asian populations due to a large amount of intermarriage between the Chinese and Vietnamese - an event which continues to occur today as many ethnic Chinese living in Vietnam get married to ethnic Vietnamese people. Contrast this with the Muong people, who have the same origins as the majority Kinh but they were never sinicized having remained largely independent by living in the mountains and are perhaps more similar in culture to the proto-Vietnamese. People often note the have Kra-Dai influence on their culture but so did the Kinh before Chinese domination.

China was a highly centralised bureaucracy and its control over Vietnam was actually quite loose for most of its 1000+ year rule. This was because Vietnam was nearly always the farthest province from the Chinese capitals which made it hard to govern. The Vietnamese managed to retain their identity and in many ways choose what parts of Chinese culture they wanted to adopt rather than have it enforced on them completely. The Chinese ultimately lost Vietnam during the Tang Dynasty not through the Vietnamese fighting against Chinese occupation but because China was more concerned with solving internal problems such as the An Lushan Rebellion (a man of Gokturk and Sogdian origin named An Lushan wanted to topple the Tang to establish his own dynasty in China). Vietnam declared its independence at this time and China was in no condition to suppress this movement.

The Chinese first took control of Vietnam to extract natural resources but they were never as interested in occupying it ever again in later dynasties as it had developed lucrative trade with other Southeast Asian kingdoms which was far easier to manage than taking over Vietnam again. So yes, Northern Vietnam WAS a part of China for over 1000 years and the Chinese had a massive influence on Vietnamese culture, language and genetics. Southern Vietnam, however, was not a part of China. It was conquered by the Vietnamese themselves from the Cham, Khmer, and other non-Vietnamese. The areas were "Vietnamized" so many ethnic minorities were forced to become Vietnamese. I am aware that many Vietnamese people are highly nationalistic and defensive of their heritage which leads to some historical revision, especially regarding the exertion of Chinese influence on the Vietnamese identity.

Andrea Nguyen says

Thank you for taking time to write such an articulate response!

Jake Nguyen says

Vietnamese Pho came from the adaptation of the French pot o fue. The vietnamese wre poor and couldn't afford the prime cut beef at the time, hence they used beef bones to create a unique dish called Pho until this day. Pot o fue is still around because it is real so as Pho becomes popular. There was no Chinese Pho even before or after the French occupation. Please you are Vietnamese don't sell our soul and culture to the Chinese.

Andrea Nguyen says

Jake, the story about pho is more interesting. I did a lot of research and this is an excerpt from my book, The Pho Cookbook.

https://www.vietworldkitchen.com/blog/2018/03/the-history-of-pho.html

As for this version of pho, it is a recipe from a Yunnan cookbook.

Windy says

You should call it chinese noodle instead of phở because phở is a traditional Vnmese dish, especially when you said adding fish sauce did not make it more Viet-ish. No wonder you made others upset because the way you wrote it is very offensive. Trust me, a true Vietnamese would not use your recipe because why cook pho the Chinese way as you call it. If I want to eat pho, I ' ll cook it the traditional Vietnamese way.

Andrea Nguyen says

Windy, this recipe came from a Yunnan cookbook. Yunnan is in China. I have lots of Viet pho recipes in my book, The Pho Cookbook. The introduction of that book is a History of Pho, which discusses the cultural intermingling that makes pho so incredibly interesting. You may read the history excerpted here.

Vinh says

What is up with all the hate? Just be comfortable with who you are and don't get so caught up with your identity because no one is trying to steal your identity. We're all humans.

Thank you Andrea for the fasinating post. And thank you Marie for the erudite response.

Andrea Nguyen says

Thank you Vinh! I appreciate your taking time to comment.

Mike Valentin says

Couldn't agree more....just be yourself and stop hating on others....

Sheryl says

Yes, stop the negativity! I love the new cookbook! I'll definitely get the other ones. Thank you for sharing your recipes!

Andrea Nguyen says

Indeed. What we need less these days is negativity. But sometimes people need to gripe so they do. Thank you for cooking and sharing your uplifting thoughts.

THI THUYEN TRAN says

Hi Andrea,

Accidentally saw the post and make me feel quite curious about the topics because I am Vietnamese, living in Madrid, Spain and I´m very interested in the cuisine and the culture too.

Firstly, I would not prefer to discuss my point of view about the country´s history (Vietnam). The history is the history and every country have their own history of forming, founding, separating, or reforming…and someone will agree with what was written, someone will not. It´s a topic that we can keep our own opinion because it depends on our own point of view, our own position, and the background we´re from. Someone studies about the culture (Cuisine is one aspect of the culture) need to keep a moderate, open-mind and respect the opposite ideas and no judge.

I would give my opinion to the point of how to call the dish which make many Vietnamese who commented your post disagreed with you.

So far, Phở is a Vietnamese name for the dish of the country which is well known and popular in Vietnam and worldwide (now). That dish may have many roots and influences during its own history of forming, but finally it became a Vietnamese-origin dish and its name only refers to that dish which we – all Vietnamese can distinguish it very easily by its taste and flavor coming from ingredients used to make it. Moreover “Phở” is not a general name for all the dish of soup with rice noodle in the world, it´s a private name like the name of one person so only that person will be called like that, not other. And here we´re talking about Phở , which, before becoming well known by foreigners, all the Vietnamese people from the North to the South of the country eat and cook it in their own way and make different version but everyone can say that it´s Phở for its taste and flavor in general (I´m from the North of Vietnam and I eat Phở in Hà Nội all my life but I can tell you we don´t eat Phở with mint and if we do, we eat with one kind of Vietnamese basil which is very local in Hà Nội called Húng Láng - similar in the form but definitely not mint- or sometimes with Basil grown in Vietnam which may be called Thai Basil due to the similarity in the taste and the form, but the most common ingredient we eat with Phở is green oinion - Hành Hoa in Hà Nội or Ngò Gai in version of Phở in Nam Định). If one dish is very far from the original taste of one dish or tastes totally differently, then it´s cannot be considered like one version of that dish. It must have another name, even it maintains some root and influence from the original dish, so all we need to do is to respect the dish and its name.

Likewise, that Yunan dish in your essay is not any kind of Phở (I used Phở, not Vietnamese Phở because Phở only exists in Vietnamese and Vietnamese cuisine and for only that dish with its varies, it doesn´t exist in any other cuisine with the same name) because it´s different from ingredients to the taste as your conclusion and I believe that you´re right in this point. Thus, there will not any so-called “Chinese beef Phở” because such that name doesn´t exist. It´s more correct to called it “Yunnan Beef Noodle” or its own name which respects its origin.

While you mentioned in your title these words “CHINESE BEEF PHO RECIPE” and many other times in the essay, then they´re not any kind of quoting from any cookbook of your friend – Georgia but they´re your own words. Moreover, using private name Phở as a general name of any soup-base dish then it´s not correct. In fact, I haven´t read the book of your friend and I will not do it 😊 so I don´t know how Georgia called her dish from Yunan, but you did read it and you knew that it´s not Phở in any sense, so firstly you should not have mentioned Phở in your own title as if it were one rice noddle-soup dish which can be found in any cuisine, it’s not true and everyone who understand the dish Phở and its origin will not agree with the way you combine it with other name to call a different dish, and me neither. So clearly, if you want to quote from other book, there need put them in quotation marks “ ” so everything is much clear and well express the idea.

In addition, from your point of view Phở has the root from China (I read another history of Phở which has a French root rather than Chinese root also other source saying that Phở is originally from one province in Vietnam….) but it doesn´t matter that much. The root is one thing but the dish itself is unique and independent. In China, I don´t know so far that they have one dish that calls “Phở” or any other dish with a compound name which contains the word “Phở”, so if Georgia called that Yunan dish is “Chinese beef Phở”, then she´s wrong and she basically did not respect that Yunnan dish which has its own flavor and history and maybe she just tried to combine that dish with one famous similar dish to make her book sell better!!!

After all, of course you can do whatever you want to make your recipe and your book more attractive to your buyers, but it should be correct and clearly for every reader to avoid the misunderstanding which might make some readers feel offensive.

Andrea Nguyen says

Dear THI THUYEN TRAN.

I stand by the "History of Pho" that I spent months to research, including interviews with people in Hanoi. It is part of my book not to make the book attractive -- but to firmly make the case that pho is firmly rooted in Vietnam. I do not take research lightly and the article specifies a well respected essay by Dung Quang Trinh, “100 Năm Phở Việt” (“100 Years of Vietnamese Pho,” 2010). It is an often-cited historical essay on the origin of pho. The article is only available in Vietnamese.

The proposal that French colonials inspired pho from pot au feu robs the Vietnamese and other native cooks of their resourcefulness and creativity. Viet cuisine owes a certain amount to French colonialism but we must be careful to give so much away. The Viets stand proudly on their own as cultural survivors. I'm not the only person to recognize that the initial pho vendors in and around Ha Noi were of Chinese descent. Chinese-Viet people are part of Vietnam's history. Chu Nom is rooted in Chinese language.

The Lao make pho, as stated here: https://laotiancommotion.wordpress.com/2013/07/22/authentic-lao-pho-recipe/

Why shouldn't there be a Chinese take on pho? Yunnan and Yuenan are neighbors.

The reason why I post recipes and discuss the movement of ideas across borders is because it is how human live. We do not exist and cook in a vacuum.

In my book, "The Pho Cookbook", I recognize the differences between Northern and Southern pho and have recipes to help people make both kinds. Pho is not an isolated food. It is meant to be shared and to evolve. In Vietnam, there are pho cocktails!

Check out the book. Maybe your library has a copy.

Thanks for taking time to write!