Asian ingredients often have either oddball names or poetic ones. For example, Vietnamese nuoc mam literally means water of fermented aquatic animals and is translated into English as fish sauce, an unpleasant sounding term that’s at least better than fish gravy, a thankfully outdated translation of our beloved condiment. Then there are intriguing monikers, such as mouse tail noodles, which have charmed and miffed me for several months now. I first encountered the chubby, short rice noodles at Layang Layang Malaysian restaurant in San Jose, CA, where they were stir-fried with belancan shrimp paste, shrimp, egg and bean sprouts. I’d never heard of them before and was smitten at first bite as each noodle is 2 to 3 inches long, about ¼ inch thick in the middle and tapered at the ends. Squiggly and squishy, the noodles were fun to eat and they picked up the flavors of the other ingredients well. They tasted rich and greasy in a good way. I thought that I knew the major kinds of Asian noodles, but didn’t recognize mouse tail noodles. Were the noodles some kind of Malaysian stealth ingredient?

Asian ingredients often have either oddball names or poetic ones. For example, Vietnamese nuoc mam literally means water of fermented aquatic animals and is translated into English as fish sauce, an unpleasant sounding term that’s at least better than fish gravy, a thankfully outdated translation of our beloved condiment. Then there are intriguing monikers, such as mouse tail noodles, which have charmed and miffed me for several months now. I first encountered the chubby, short rice noodles at Layang Layang Malaysian restaurant in San Jose, CA, where they were stir-fried with belancan shrimp paste, shrimp, egg and bean sprouts. I’d never heard of them before and was smitten at first bite as each noodle is 2 to 3 inches long, about ¼ inch thick in the middle and tapered at the ends. Squiggly and squishy, the noodles were fun to eat and they picked up the flavors of the other ingredients well. They tasted rich and greasy in a good way. I thought that I knew the major kinds of Asian noodles, but didn’t recognize mouse tail noodles. Were the noodles some kind of Malaysian stealth ingredient?

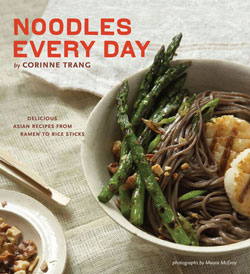

For months, I’d look for mouse tail noodles at Chinese markets, in dried and fresh form but never came across them. My God, did the restaurant have someone make them by hand in an undisclosed location in San Jose? That didn’t seem right. The mystery didn’t get resolved until I got a copy of just-released Noodles Every Day (Chronicle Press, 2009) by acclaimed Asian cookbook author and cooking teacher Corinne Trang.

Organization, Highlights and Surprises

Noodles Every Day leads cooks through Asia’s major noodle offerings by organizing them by noodle type – wheat noodles, egg noodles, buckwheat noodles, rice noodles, and cellophane (glass) noodles. There’s a closing section on buns, dumplings, and spring rolls because those types of foods are often paired with noodles. Corinne pours her rich background into Noodles Every Day, weaving in her Chinese-French-Cambodian-Vietnamese-Indonesian-American life experiences into the recipes, thereby fostering a cross-cultural understanding of Asian noodles. She blends her enthusiasm and humor with well-honed practical knowledge into the instructions, whether they’re for preparations of childhood favorites or adult discoveries.

As a single subject cookbook, Noodles Every Day enables noodle lovers and Asian food aficionados to explore an integral part of the region’s culinary traditions. Served hot or cold, noodles can be featured in soup broth, stir-fried, salads, and fillings, and Corinne guides readers through the many options, opening our eyes to the delicious possibilities at every turn. It’s hard to keep all the noodle types straight and this book clarifies the differences, for example, between Japanese somen, udon, soba, and ramen. I didn’t know what the names of the various Chinese noodles are, and Noodles Every Day presents the names -- lao mian, shiazi mian, and dan mian, for example, so that I can ask for them at markets or restaurants. Corinne’s descriptions of the various noodles are precise and helpful, but they are unfortunately not accompanied by actual photos, leaving it up to readers to imagine what a noodle looks like at the market place. Extrapolating from the recipe photos is doable, but I wish that there had been space allowed for ingredient shots.

Nevertheless, there are some great surprises in this collection of more than 70 recipes. Corinne discusses the use of instant ramen noodles, a gutsy but realistic move since instant noodles are a valid eating option in much of Asia. (Lord knows, I've eaten instant pho noodles.) I’ve seen packages of dried shrimp and crab-flavored noodles at Chinese markets but didn’t quite trust them to have much to offer. Corinne catches my attention when she suggests preparing the noodles with shrimp and a velvety crab sauce, respectively, to compliment the delicate flavors of noodles. This makes utter sense but I wouldn’t have thought of it had I not perused Noodles Every Day.

Mouse Tail Noodle Mystery Solved

After reading the rice noodle chapter introduction and looking at the photo of Corinne’s stir-fried silver pin noodles with chicken, bean sprouts and scallion, I had another “A-HAH, DUH!” moment. The mysterious mouse tail noodles are the same as silver pin noodles, called nen dzeem fen in Chinese. I’d seen those noodles at my Chinese market. I’d always passed them up because they were mislabeled banh bot loc in Vietnamese, which normally denote a wormlike tapioca noodle used for preparations such as jackfruit, toddy palm, and pomegranate sweet soup (che Thai).

On my next trip back to Lion Foods, I picked up a package of fresh ‘banh bot loc’ in the refrigerated section. The ingredient listing included rice flour, wheat starch, and water – no tapioca starch. So these were the mouse tail noodles, the silver pin noodles that I’ve wanted. They were under my nose all along. This discovery, along with many others, is what makes Noodles Every Day a worthwhile addition to my cookbook collection. Good cookbooks provide new ideas and unexpected knowledge, and this one delivers.

Next up: Cooking with silver pin noodles using Noodles Every Day

Annie says

Isn't it great when you finally figure out what you're looking for? For the longest time I was looking for this leaf (daun kadok) that is used in a Malaysian dish called "otak otak" and your cookbook with its treasure of pics of Vietnamese herbs came to my rescue! Unfortunately, I still have not located it in my local asian store (maybe I'm not looking hard enough) and I'm about to head back to Malaysia so I figure I won't need to make it myself!

Oh, btw, I never knew these noodles as "mouse tail noodles," they were always "loh shi fun" to me. LOVED it as a kid and still do today though cannot get it as readily even in Malaysia (when I was younger there was a scare on some ingredient found in that noodle and it lost its appeal and even today, the noodle hasn't ever gotten back the favor it used to have).

Andrea Nguyen says

Annie, that's great. Boy, have you been to Thien Thanh market at Keyes and Story? They'd have the Vietnamese herb, I believe.

As for "loh shi fun" -- I just looked up the characters, which are 老鼠粉 and roughly mean:

old = lao/lo/老

rat/mouse = shu/suy/鼠

noodle = fen/fun/粉

So to be exact, I suppose we need to call them old rat/mouse noodle. Somehow, I don't think that will sell. . .

wayne wong says

Your break*down* of loh shi fun, Andrea, broke me *up*! lol! While "old rat/mouse noodle" isn't likely to become the next culinary catch-phrase, your collegial review of "Noodles Every Day" is undoubtedly boosting its sales. Hopefully Corinne will return the favor tenfold when your long-awaited "Asian Dumplings" is released in August.

Jim says

Daun kadok is also known, perhaps more so, in some parts of the world as Daun laksa. It's referred to in Oseland's "Cradle of Flavor" as well as Terry and Christopher Tan's excellent 2003 book on Peranakan cooking, "Shiok!" where it is prominently featured on the cover. Although many good herb books abound, I'd like to find one that thoroughly incorporates alternate herb names from around the world. Maybe it wouldn't have taken me so long to realize that Puerto Rican culantro, Vietnamese ngo gai and Trinidadian shadow bennie were all the same thing...

Andrea Nguyen says

Wayne -- I used to spend hours/days studying Mandarin and breaking down characters for food is one of my geeky pleasures. It allows me to pour all the weird skills I've amassed over the years into food.

Jim -- Love it that you've brought up two of my favorite Southeast Asian cookbooks. Yes, daun laksa is known in Vietnamese as rau ram; I'd only had it as laksa in the herb primer page referenced below. Indeed, a truly comprehensive work is what we need! I didn't zoom in that rau ram was also daun kakok and just added it to the Vietnamese herb primer page listing of rau ram:

http://www.vietworldkitchen.com/blog/vietnamese-herb-primer.html#cilantro

Thanks, gentlemen!

Lan says

Thank you Andrea for also listing the scientific names on the Vietnamese herb primer page. No matter where you are in the world, at least the scientific names can be used for cross referencing.

It can be difficult sometimes when "experts" mistranslate ingredients. One episode of Gourmet's Diary of a Foodie had a contributor on Vietnamese food translate rau ram as knotweed and pomelos as grapefruit. I'm also puzzled by the show's Vietnamese recipes using lemon verbena but recommending lemongrass as a substitution.

I think that is one of the reasons Martin Yan has such mainstream appeal. He takes great care to make sure his translations for ingredients are accurate.

Annie says

No, no, daun laksa is totally different from daun kadok. Please don't change it. Daun laksa is rau ram which I can easily find in our Asian grocery stores. Daun Kadok is a much greener, larger beast. Totally different.

Annie says

I just looked at your primer again, and I think daun kadok is the wild betel leaf. I'm not 100% sure so don't quote me on that but I'm almost certain that that is the one and that is the one I have a hard time hunting down at the stores.

Supra TK Society says

Patience and application will carry us through.

coach outlet malls says

In my opinion, most certifications (i.e. Microsoft, A+, etc.) are useless pieces of paper that, at most, show somebody spent some time scanning through books or sample tests and can regurgitate answers to questions that might appear on a "certification" exam.

Hands-on industry experience is far more valuable and useful in the real world. It proves (1) that you indeed possess sufficient knowledge of a given topic/technology, and, (2) if you are confronted with a problem or situation in which you lack expertise, you are resourceful enough to obtain (whether it be via colleagues, reading manuals, conducting web research, calling vendor support, etc.) the information necessary to arrive at an effective solution.

Taobao English site says

nous n'avon pas la hannuka ici en Brésil..#

Agoniirrido says

sDdqOrrEs new england patriots jersey hIqvUcdWx http://zroolooks.com/blogs/entry/buffalo-bills-jerseys-01qv

marlon says

I just looked at your primer again, and I think daun kadok is the wild betel leaf.