For years now, I and other Bay Area food people have asked

For years now, I and other Bay Area food people have asked

chef/restaurateur Charles Phan this question: When will you have a cookbook? If

you don’t know Charles, he and his family

own and operate one of the most successful and high-profile Asian restaurant

empires in the U.S. Their flagship establishment is San Francisco’s Slanted

Door, an 8,000-square foot space located not in the city’s Little Saigon but

rather the Ferry Building — the iconic epicenter of the

Bay Area’s local and artisanal food movement. As one of San Francisco’s top culinary destinations,

Slanted Door announces that modern Asian food has arrived.

On a nightly basis, Slanted Door is packed with foodies,

tourists, and suits feasting family style and relishing Vietnamese dishes. What

attracts diners are the tight, ingredient-driven menu, inviting ambiance, and

professional service, not a kitschy, themed experience. In fact, the sleek

design of stone, wood and glass echoes the panoramic view of the rugged bay. Other

than the faint whiff of nuoc mam, the

environment doesn’t give away Slanted Door’s Vietnamese identity. By

transcending preconceived notions of race and ethnicity, the restaurant is

refreshingly post-ethnic, as dynamic and organic as Asia

itself.

So when Phan’s debut cookbook arrived, I had certain

expectations. Never mind that he collaborated with Jessica Battilana on the

book. That’s what many chefs do these days. Jessica is a very able writer

tasked with recording and conveying his words and recipes.

Most restaurant chefs first release a book about their

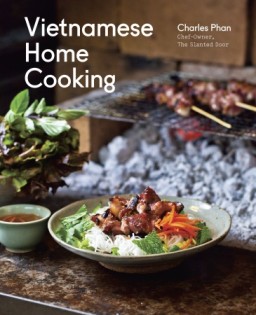

establishment. Phan’s first book is surprisingly broadly titled, Vietnamese Home Cooking.

A slew of shock-and-awe travel shots of him in Vietnam open

the book. They then segue into images what appears to be Phan's home in the Bay Area. There

are few obvious photos of the Slanted Door, despite the fact that a fair number

of recipes come from the restaurant and/or reference cooks there. Chefs coats

and latex-gloved hands signal a professional cooking environment, not a home

kitchen.

At first glance, Vietnamese

Home Cooking seems perplexing, perhaps because it aims to fill too many

needs.

Mixed Purposes and Messages

Location shots of Vietnam evoke the edgy adventurousness of David Thompson’s Thai Street Food but recipes aren’t purely

from the motherland. Phan’s recipes don’t always tie back to his travels in

Vietnam, which if you’ve been to Slanted Door and/or followed his career, you

totally understand. Phan emphasizes cooking with local resources. Slanted Door’s

mantra has been to convey the soul of Viet fare with a Bay Area sensibility.

Recipe food shots are sometimes from Vietnam but the recipes themselves don’t replicate

those images; Phan admits so but readers use food photos not only to dream but

also to reference and copy.

At the outset, Phan emphasizes conveying knowledge about

Vietnamese aesthetics. (Slanted Door is a stunning, well-style restaurant

because Phan attends to minute details. He loves wood and used to be a potter. Slanted Door's food is served on local Heath

ceramics.) Phan also wants to present fundamental Vietnamese cooking

techniques yet recipe chapters are unevenly titled: Soup, Street Food, Steaming,

Braising, Stir-Frying, Grilling, and Frying. These are not comparable

categories.

The soup chapter (consider it the “simmering” chapter, if

you like) leads with a selection of stocks and complex noodle soups, followed

by simpler, everyday preparations. I wish that the order was reversed so that

cooks could dip their toes into the Viet water before diving in. Phan correctly

says that many homes in Vietnam lack ovens yet the beef stock recipe calls for

roasting onion in an oven for a hour. That’s technique should have been

explained, especially because the stock is used for pho broth, which

traditionally calls for roasting the aromatics over an open flame.

The street food chapter seems out of place in a book on home

cooking because in general, those foods are specialty foods that vendors master.

But more importantly, the street food recipes could have been slotted per

cooking techniques in the other chapters. And vice versa. Dumpling and bun

(bao) recipes in the “Steaming” chapter are street foods, as should the noodle

soups. In fact, the street food chapter introduction includes a photo of Phan eating

what looks like bun bo Hue noodle

soup but that recipe is in the soup chapter. Vietnamese Home Cooking wants to call out noodle soup and street

food -- beloved, go-to dishes that readers know from travel and eating out. But

the book’s technique-oriented framework makes that goal awkward to achieve.

Chinese-Vietnamese-American

Approach

Phan’s recipe collection reflects his background. His family is

ethnically Chinese, a point that he makes in the daikon rice cake recipe

introduction (page 70), one of many Chinese recipes in Vietnamese Home Cooking.

The Chinese have influenced and exchanged ideas with the

Vietnamese for millennia by virtue of location and most notably through nearly

1,000 years of colonization. Phan’s father fled from Southern China to Vietnam

to avoid the oppressive Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976). Eventually their Chinese-Viet

family escaped Vietnam’s political upheaval in the 1970s and resettled in San

Francisco, an area with a substantial Chinese population. Recipes such as the

daikon cakes (a dim sum fave), Chinese donuts/crullers (dau chao quay in Vietnamese), lacquered quail with Sichuan cucumber

pickles, southern Chinese lo soi

braised pork reflect Phan’s Chinese roots.

There’s a sweet-and-sour fish dish inspired by a Phan’s

engagement banquet in Thailand, where his wife was born. Ingredients such as

porcini mushroom powder and curry leaves offer glimpses into how Phan and the

Slanted Door incorporate non-traditional ideas in their Viet fare. Beer-battered

soft-shell crab references Zabar’s in New York and employs Viet fermented

anchovy sauce. Overall, the recipe collection tells the unique story of Phan

and the Slanted Door, as one of immigration and the unfolding multiracial American culinary

landscape.

Random Errors

With

all the accent marks (called diacritical marks), Viet language is tricky to

correctly spell. Choosing the right font to present the terms and proofreading

are among the issues of publishing about Viet topics.

To skirt the issue, Vietnamese

Home Cooking does not offer a Viet

name for most recipes and ingredients. Nevertheless, diacritical marks show up on

a random basis. Sometimes, such as in the case of “pho gá” [sic], it should be spelled phở gà to be fully correct or pho

ga to omit the diacritics altogether. Chicken pho would do too because pho,

like banh mi, have both become part of the English dictionary. You don’t have

to italicize them. (Hurray.) However, if the words are presented next to a Viet

word dressed with diacritical marks, you have to go all the way. Phan’s hometown

is misspelled as “Đà Lat” [sic]

when it should be Đà Lạt, Da Lat or Dalat.

Spelling quibbles aside, Phan presents a few ideas that confound

and confuse. His halibut vermicelli with dill and pineapple-anchovy sauce pairs

a northern Viet classic with a southern Viet sauce. Mam nem, a sludgy anchovy-based fermented condiment is mistaken for

mam tom (mam ruoc), a pasty

shrimp-based fermented condiment. Both are stinky but their funkiness are not the

same. In 2010 when I went to Cha Ca La Vong, the Hanoi restaurant that’s often cited

for its rendition of the dish (Phan gives his nod to it too), diners are

offered sauces made with mam tom and nuoc mam, not mam nem.

Lotus leaf-wrapped sticky rice is described as a must-have

for September harvest festivals, particularly the dragon boat festival.

Phan’s recipe is for steamed Cantonese lo mai gai

(nuo mi ji in Mandarin) packets

served at dim sum. For dragon boat festivals, it’s the slightly conical-shaped

Chinese zongzi dumpling of boiled sticky

rice wrapped in bamboo leaves that are

cast into the water. [10/27/12: In Vietnam, zongzi are called banh tro and typically wrapped in bamboo leaves and tied up just like the classic Chinese ones; abroad, you often see them for sale at Vietnamese delis and markets. However, I just found out that zongzi are sometimes wrapped in lotus and banana leaves so perhaps that rendition is what the recipe in Vietnamese Home Cooking refers to. If you'd like to see how zongzi are wraped, jump to this post on Asian Dumpling Tips.]

Readers unfamiliar with Vietnamese and Chinese culture and

foodways would not detect these points. However, if Phan aims to teach people

something, then being accurate matters.

Gems in the Pages

Given my comments about Vietnamese

Home Cooking, why look at the book? In my home, I’ve renamed it The Slanted Door Cookbook because that’s

what it really is, a restaurant book. Restaurant cookbooks give readers

insights into little tricks of the trade and approaches to food that you can

glean from. In my case, I was intrigued by a DIY recipe for bun rice noodles

that Phan presented. When I was in Seattle, I got to see how the pros made banh

cuon rice noodle sheets at Van Loi Noodle Factory. We were too late for the bun rice

noodles so my curiosity lingered. Phan offered instructions for homemade versions that I tried. (More on

that here soon.)

Slanted Door adds salt and sugar to their scallion oil, a

trick that I’m going to try. Their roasted chile paste isn’t traditional Viet

cooking but it looks tasty. The Phan family’s ground pork with salted fish

seems like great Chinese homey fare. A yuba (tofu skin) dumplings with miso

broth recipe intrigues me, though it’s obviously not Vietnamese.

If you’re interested in one of the premier Vietnamese

restaurants in America, check out Phan’s cookbook. Vietnamese Home Cooking contains

interesting takes on Asian food that are worth considering.

Have thoughts on the book, restaurant, or Vietnamese food and cooking? Share them below.

Related posts:

- Bun Rice Noodle Recipe Project (+ a video tip)

- Zongzi wrapping lesson from a master (on Asian Dumpling Tips, if you're curious about how they come together)

- 2009 Review of Asian Cookbooks (including Thai Street Food by David Thompson and Songs of Sapa by Luke Nguyen)

- How Banh Cuon Rice Noodle Rolls are Made (+ video) (at Van Loi Noodle Factory in Seattle)

Mike says

I sincerely doubt anything can top your book.

Andrea Nguyen says

Mike, you're too kind. I wasn't looking to top "Vietnamese Home Cooking" but am always advocating for solid info on Viet food and cooking. All that said, thanks for the pat on the back.

Bee says

Andrea, I have the cookbook and I will be honest: I liked it but don't love it. I was a fan of Charles Phan when he first started out at the small restaurant and before I tasted the goods at Little Saigon in Orange County. I have never been to the new ones. I thought it wasn't really Vietnamese Home Cooking as you mentioned, many of the recipes are not Vietnamese. On the other hand I actually like Little Vietnam, a much smaller book by Tuttle from a Sydney-based restauranteur. All the recipes in Little Vietnam I wanted to eat, not so much from Phan's book. 🙂

Rita says

I had been looking forward to seeing this book, but when I picked it up at the bookstore a few days ago I was tremendously disappointed. I found it chaotic. What do all those pictures have to do with the cookbook? I found the layout and formatting of the text distracting and awkward to follow. Like you, I found the ordering of chapters and recipes illogical and inconsistent. Some of the recipes struck me as not quite right. I was surprised at the number of Chinese recipes in the book. Your explanation of his background puts it into context. There are lots of Chinese Vietnamese here in Portland, but all whom I know had much deeper roots in Vietnam.

I'm not Vietnamese, but we fell in love with Vietnamese food back in the 1970s. I have a fair number of Vietnamese cookbooks. The ones I find most helpful for unfussy home style food are your Vietnamese Kitchen book and Vietnamese Cookery by Jill Nhu Huong Milller and The Classic Cuisine of Vietnam by Bach Ngo and Gloria Zimmerman. I don't think either of those two are still in print, but they are available used.

By the way, your Asian Tofu is great.

Andrea Nguyen says

Bee, thanks for the honest assessment of Vietnamese Home Cooking. Knowing your audience and/or writing for a particular audience makes for a tight, well-done cookbook. Phan's book has lots, if not too much, going on. That makes for a distracting publication.

Andrea Nguyen says

Rita, thanks for sharing your gut reactions to the book. It is chaotic, totally contrary to what Slanted Door is like. The number of Chinese recipes could be interesting if they were put in context.

maluE says

andrea, i admire how you so kindly reviewed this book and explained its value in context .. we were phan fans from his earliest days in his Mission district restaurant - entertained virgin-to-vietnamese visitors there .. we followed him to his interim location farther down on the waterfront, where we began to be disappointed - the food seemed more flash than substance .. because we love the SF Ferry Plaza and show it off, we've been to Slanted Door there many times - mixed reviews .. veterans of the cuisine say much better and less expensive vietnamese food can be enjoyed elsewhere in the bay area .. we still go only because we're there already, it's a nice room and ambience, the service is good enuf .. i've been wanting to share my thoights with mr. phan - that maybe with his sudden celebrity, he lost touch with his original mission in the Mission?

Perry Atkins says

Love the Slanted Door for eating out, but it's your cookbook Vietnamese Kitchen, that I reach for at home.

Andrea Nguyen says

MaluE, It's indeed hard to go from a small neighborhood place to the Delancey temporary spot to doing about 800 covers (orders) in 8,000 square feet. There have been times when I've seen the wok station cooks at the Ferry Building location look like they were on the brink. It's a lot of work.

Chef/restaurateurs know how to run eating establishments. They may not know how to put a book together well. In Phan's case, he and the Slanted Door group may have waited too long to release a book. It's as if they were trying to do too much and that lack of clear focus produced a somewhat muddled book. Left me scratching my head at times.

Andrea Nguyen says

Perry, you and your family are too kind! Thank you.

Duc says

Andrea, to be frank, I find it unpalatable that you would write a negative review about another Vietnamese cookbook. I understand your intentions are likely innocuous, but still, it is not the classiest of moves. It is your prerogative to express your opinion and share your thoughts with your audience but as the saying goes, if you don't have something nice to say.... I just find it unkind and unnecessarily divisive. I've no doubt your commentary on the book is valid, but to what end are you achieving by posting them so publicly?

Quyen says

Andrea,

I really appreciate your review of this book. There aren't enough Vietnamese cookbooks at my local library, so I often purchase books just to discover that they are duds The books I reach for frequently is yours and Nichole Routier (from my mom). I've tried almost every recipe in both books.

Maggie says

Andrea, you make an interesting point about accuracy. I do appreciate when authors go the extra mile to enlighten readers about authentic ingredients, the rationale behind techniques and culinary traditions. Understanding the 'building blocks' of any cooking style helps home cooks to make confident substitutions when ingredients are hard to come by (not everyone lives in SF or NY!), and it is helpful when authors care enough to suggest acceptable alternatives. I'm thinking of Fuchsia Dunlop's new book on Chinese home cooking, which is intelligently authentic and informative, a real gem. Having said that, I think there is ALWAYS a place for innovation, especially when it comes to food. Your critique of this book's Chinese influences seem harsh (OK, the title of his book may be misleading for some, a pleasant surprise for others, perhaps). For me, no recipe is sacred, and rules are made to be broken - there is much to be said for shortcuts in traditionally labour-intensive cuisine. As long as the results are tasty! Perhaps you would recommend Mr Phan's book for people who have already mastered Viet cuisine?

Maggie says

Actually, I've just been checking this out on Amazon. It looks really good (I know little about Vietnames cuisine), especially the chapters on soup and street food. Thanks for drawing my attention to this book!

Andrea Nguyen says

Duc, thanks for your response. This is not a negative review as I have made statements about the importance of the restaurant in America's culinary landscape. Please see the lead paragraphs. I have been fair in my assessment. I am a staunch advocate for Vietnamese food and culture. I don't believe in staying quiet all the time when there are glitches that can't be overlooked. Finally, the closing of this post encourages readers to check the work out.

Andrea Nguyen says

Maggie, I totally agree about innovation and modern takes on cooking. In "Vietnamese Home Cooking," there is seldom context provided for the Chinese dishes in the recipe collection. They're ones that are dear to Charles Phan and his family but are they representative of the Vietnamese repertoire? Authors carefuly curate their recipe collection so that it fits their work's aims. That's why in the main, this is a "Slanted Door Cookbook" or "Slanted Door at Home" cookbook. There are lots of interesting recipes, as I mention in the closing of the post.

Andrea Nguyen says

My pleasure.

Andrea Nguyen says

Thanks, Quyen. There's always room for more Vietnamese cookbooks. And, I don't have to write them. Seriously.

Maggie says

Thanks for taking the trouble to reply, Andrea. I can understand how traditionalists might object to the somewhat misleading title. It raises the question of what 'authenticity' means in today's shifting culinary landscape. As a Chinese, I'm not particularly interested in cookbooks that promise to show me how to recreate restaurant 'favourites' such as sweet and sour pork or lemon chicken, yet they are still 'Chinese' cookbooks. If I'm cooking for friends and family at home, I might stir some Roquefort cheese instead of the traditional 'fu ru' into wilted spinach, or use some salty black couchillo olives instead of fermented black beans in a stir fry. I might even substitute homemade duck confit (more painstaking, and healthier than the boil-and-deep-fry affairs offered in most restaurants) into 'crispy aromatic duck' pancakes. Does that make my meal less 'Chinese' or less 'homesytle'? For me, no, because I believe the spirit of Chinese home cooking lies in a combination of balance, healthfulness, frugality (using small amounts of strong tasting ingredients to pack a punch), and making the most of what ingredients are available. Fuchsia Dunlop, on her blog, has this to say about 'traditional' sharks fin on the Chinese banquet table: "...the point, or half the point, of ordering shark’s fin is to offer your guests something fabulously exotic and extravagant. My hope is that people who have in the past ordered shark’s fin for this purpose will be able to achieve the same frisson of excitement with a bottle of vintage Bordeaux – or, for that matter, with some marvellous wild, free-range, sustainable venison from a particular estate!" How refreshingly inauthentic! From what I gather, Mr Phan is commited to using locally available, quality ingredients in his food, without the 'crutch' of MSG that is common in so much Asian cuisine, and it seems churlish to criticize his book as not being the real deal.

Andrea Nguyen says

Maggie, kudos to you for adding twists to your food. The roquefort is a terrific sub for bai fu ru. I advocate for twists but also recommend that cooks have solid foundations in the fundamentals. I've taken these stances on this site and in my cookbooks.

My comments about "Vietnamese Home Cooking" is that the recipes are more representative of Charles's personal experience and what is served at the restaurant, not what most Viet people consider to be in the Viet repertoire. That said, there are many great ideas to glean from the book as I point out in the last section of the post.

The Phan family story is a unique and fascinating one in the American culinary landscape. I wish that it was told more clearly in his book.

Maggie says

Yes, it would be fascinating for some people to hear how Charles Phan's personal history has influenced his food. But do most people who enjoy Pho realise that it's origins lie in the French dish 'pot-au-feu', or that Banh Mi comes from 'pain de mie'? Does it matter? My family have been enjoying egg tarts forever, with no inkling that they most likely evolved from the 'nata' brought to Macau by the Portuguese. Now I'm being churlish! Thanks for the interesting discussion, Andrea.

Rbullock says

Thanks Andrea for a really thoughtful review. Maybe the title was the publisher's? Anyhow, while Slanted Door has had a huge impact on the place of Asian cuisine in the Bay Area/the US, that doesn't render the book above/immune to all criticism!

Andrea Nguyen says

I don't know all the details of the publication. Thanks for taking a read and commenting. I try to be honest in my book reviews, constructive criticism, praise and all the stuff in between. I don't often sit on the sidelines.

Anna says

I have to say that I find this review quite helpful and eye-opening. I am Georgian (former USSR) and I find it more than a little annoying when my country's cuisine is erroneously lumped in with Russian cooking. Someone who is not born into the cuisine may not pick up on this but cookbooks which advertise a particular ethnic cuisine should be true to the style and say so when there are other influences involved. Non-Vietnamese readers are unlikely to pick the Chinese threads, etc that are scattered through the book and it is nice for someone to educate us on the differences. I do not think the tone was derogatory and I do not think that people of the same ethnicity have an obligation to support each other over all else, forgetting authenticity.