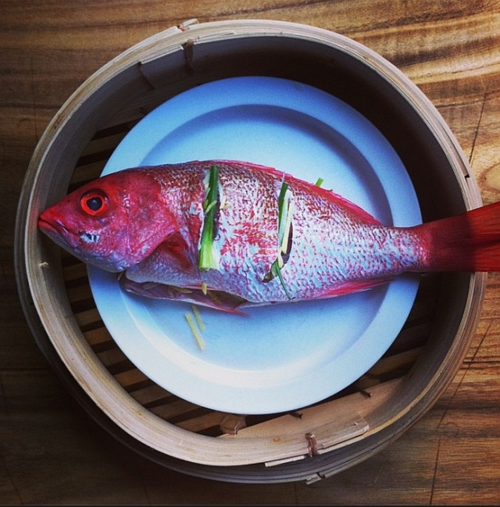

I posted this photo of fish that was destined to be steamed. My initial point was that the snapper was kissing the steamer and I needed to trim its tail. Before I snapped the photo, I arranged the fish so it would look handsome. The belly was gutted in a manner that made the fish look unpleasant had I positioned it pointing to the left.

Nanette, a former resident of Japan who now lives in Hawaii, tweeted that the Japanese like their fish presented with the head pointing to the left, and that they packed their fish that way. It seemed fussy to me and during my limited time in Japan several years ago, I didn’t recall the fish heads all pointing the same direction. I was researching tofu so perhaps I missed something. I reviewed my photos from the 2010 trip and alas, the fish were beautifully arranged but not necessarily pointing to the left. At markets in Tokyo, the heads pointed away from the customer (it’s often the same in the US). I suppose if I turned these boxes sideways, the heads would all be pointing left:

To figure out this cultural practice, I aske my friend Yukari Sakamoto, an author, chef, sommelier based in Tokyo. Her husband, Shinji, is a fishmonger and former seafood buyer at Tsukiji fish market. The couple leads food tours and hope to open a cooking school soon.

Shinji was attending the Tsuji Culinary Academy to study washoku (Japanese cuisine). The couple hopes to open a cooking school next year. Keep up with Yukari and Shinji via her website and seasonal food blog where you’ll see whole fish all pointing to the left:

The day after I asked Yukari for help, a speaker from the Ministry of Forests and Fisheries guest lectured at Shinji’s school. Naturally, Shinji asked about the head to the left issue.

The speaker revealed that the practice of presenting the fish in such a manner dates back to a time long ago. The Japanese believe that the fish looks best when its head/eyes are to the left and the tail is to the right. That is why seafood is usually presented that way to diners.

Interestingly, many fishmongers also follow that belief: when they are packaging fish in a box for sales or for delivery, the heads are usually placed to the left, Yukari wrote. There’s tremendous respect for the harvest from the ocean so such a practice is often carried out from the boat all the way to the retail shop. Or, at the very least, from the wholesale market to the retail or restaurant.

Shinji added that the fish is almost always served with the eye on the left, that at the retail shop (where he worked during most of his professional career as a seafood expert), “the fishmongers were careful to always keep the fish facing to the left. That way, if the fish were to be bruised, then it would be on the backside of the fish, that the diner would not see.” He also noted that Japanese fishmongers “treat fish like they are their children”.

One of Yukari’s friends suggested a religious explanation: one of the Japanese gods was born from the left eye of someone (neither ladies were sure of who is was or when it happened). [Update -- see Tomixrider's comment below for the answer.] However, as a result, the left eye is respected and usually what is facing up to the customer when serving whole fish.

Yukari mentioned Elizabeth Andoh discussing the fish to the left notion. I own all of Elizabeth’s cookbooks and in Washoku, she wrote:

As I have pointed out, when the Japanese present whole fish at table, they position them with the head facing left, the tail to the right, the belly forward, and the back away from the diner. Certain flatfishes that live on the ocean floor, however, may be reversed. Unlike round fish, which have one eye on each side of their head, flat fish have both eyes on the top of their head. Depending on the species, the eyes could be facing right or left when the belly is facing forward and the back is away. When placing flatfish on a plate to serve, arrange the fish with the top side (with the eyes) facing up, the belly forward, and the head point to either the right or the left.

I was struck by the level of detail and respect that the Japanese have for nature. There’s a high level of care and respect. Washoku – what Shinji is studying and Elizabeth espouses, is about harmonization of what we eat and how we nourish ourselves. There is rhythm and seasonality, grace and determination, aesthetics and nutrition. There’s also balance and flexibility.

After all, if you have a flat fish like a flounder sole, you can go either direction. Elizabeth explains that washoku may be a Japanese culinary philosophy but it may be practiced in many cultures. It's a very organic, natural way of eating and living. We may be doing it by instinct and not realize it. In the Vietnamese kitchen, for example, a good meal is comprised of food with multiple flavors, colors, textures and cooking methods. Pairing soup with a salad or sandwich makes for a complete meal.

Back to the Japanese notion of presenting fish pointing to the left. It's an interesting cultural preference. It works if people along the supply chain cooperate -- from the fishermen to the retailer to the cook. That level of cooperation speaks volumes to the Japanese sensibility.

However, for those of us who live outside of Japan where such a seafood consciousness does not prevail, it’s more practical to consider the aesthetic of a whole fish as we position and arrange it for diners to react positively at the table. I imagine that that is the essence of washoku.

Thank you Nanette and Yukari for opening up this door to greater seafood appreciation.

Do you have a position on this?

Related post: If you now hanker for a Japanese fish dish, try this old school stovetop salmon teriyaki. No whole fish needed.