Forty years ago on April 23, 1975, my parents were quietly saying goodbye to their Saigon home. Mom finished ripping apart the life jackets that she’d sewn for our family’s boat escape from South Vietnam, which would eventually fall to the northern communists a week later. Between the Styrofoam pieces in each of the seven life jackets were thin taels of gold. We were no longer able to leave by boat because the government forbade all non-official boats from departing. She and my father’s hope was to flee by plane the next day. The gold was among our currency. The Vietnamese currency, the dong (VDN), was worthless.

To appear as if we were going on an overnight family trip, my parents packed the absolute minimum. A set of pajamas and underwear for each person fit into two attache-style briefcases (think a large computer bag). A few pieces of valuable jewelry, family photos and the gold went into a clutch-style purse that my mother made by removing a flap from a leather purse that her sister in Paris gifted her. The clutch fit inside a tote bag, in which she had a couple small bottles of water, a few packages instant noodles, and a thin orange notebook of handwritten recipes.

“Gia Chánh Của Mẹ” roughly means “Mom’s Book of Domesticity”. Gia chánh is the Viet term for housekeeping, home economics, housewifery – that is, how to manage a home. My mom kept house well, having managed employees for decades. Plus, she knew plenty about cooking herself.

Her handwritten book contained recipes that she or my sisters gathered from Saigon newspapers, friends and elsewhere. My mother brought the book with her to America because she envisioned her new life involving owning a Vietnamese restaurant. Naturally, she needed her personal recipe collection. The notebook -- a flimsy version of today's composition books, was one of her prized possessions. Like the gold, it was part of our family's survival kit.

Mom started keeping the notebook in the early 1970s with an entry for pomelo (grapefruit) salad taken from a newspaper. When a friend shared a recipe with her, she often noted the contribution in parenthesis that it came from Mrs. So-and-So. Sometimes there was a good stories attached to a recipe. Yesterday, my mom easily slipped into a couple of orange notebook stories.

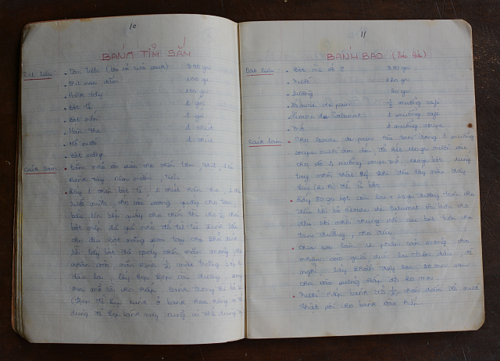

Near the beginning of the notebook is a bao dough recipe. Mom said that it came from Auntie Minh, a colleague of hers at USAID, a extension of the CIA in 1970s South Vietnam. Auntie Minh (not really a relative of ours but addressed by a term of endearment) was Chinese-Vietnamese.

Auntie Minh’s father was from northern Vietnam, Hai Phong to be exact, a marker of cultural legitimacy to Mom. He was schooled in traditional Chinese cooking methods but never got to formally practice his craft as a professional chef. Instead he taught his daughter precise cooking skills. My mom recalls that that to properly hand chop meat into perfect tiny dice, Auntie Minh said that you had to meticulously chop with your cleaver then turn your cutting board 90 degrees. That’s what her father taught her.

Such precision flagged Auntie Minh as a thoughtful, knowledgeable cook. My mom wanted a Chinese bao dough recipe and found her source. Auntie Minh’s recipe is similar in ingredients as the one I use today. The recipe is attributed to Mrs. Buu, which my mom is likely wrong because it belongs to Auntie Minh. My mom worked at USAID for years and she obtained some of her best recipes from work colleagues. “It just wasn’t at work. My friends and I shared cooking finds and tips all the time. That’s what we did,” she told me.

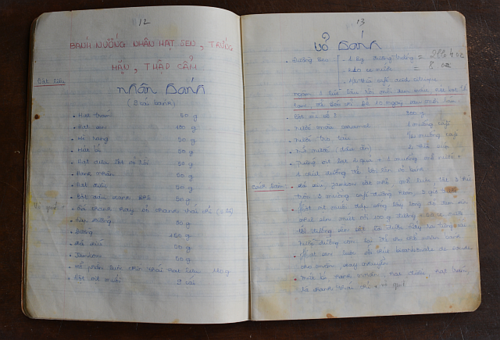

Then there’s epic moon cake recipe that spans four pages. In Saigon at the time, there was a legendary cooking teacher and writer named Mrs. Quoc Viet. In 1972 she offered classes to Saigon ladies on how to make banh nuong baked moon cake made from wheat flour and unbaked banh deo made of rice flour. They were tricky recipes full of Chinese secrets but my mom, her older sister Bac Bac and friend Mrs. Thai were determined to learn.

The price of each class was 500 dong, a relatively large amount of money back then. Skyrocketing inflation made valuing things very difficult. For example, between 1964 and 1972, the price of rice rose 1400 percent. In 1972, A South Vietnamese soldier’s salary and compensation of 7,500VDN was worth roughly 18USD. With such economic uncertainty, who could afford to take a cooking class? Who had the gall to charge so much?

“Our plan was to split up,” my mom recalled. “Two of us would learn the more intricate baked banh nuong and the third person would learn the softer banh deo. But Mrs. Quoc Viet said each person had to pay for both. So Bac Bac and Mrs. Thai attended both. I was the designated driver so I waited in the car. When Mrs. Quoc Viet relented and offered to let me into the class, I refused on principle.”

On breaks from the class, Bac Bac and Mrs. Thai would report to my mom on what they learned. After class, the three women gathered up all their notes and wrote them down. Then they invited the students and teachers from the Trung Vuong School for Female Students, where Bac Bac had been an instructor.

“Fifty women gathered in Mrs. Thai’s house,” my mom gleefully recounted. “We showed everyone how to make the cakes and shared the recipe. It was a great time. We got back at Mrs. Quoc Viet!”

Mom, her sister and Mrs. Thai had an experience equal to the $250 Neiman Marcus cookie recipe. My equivalent is the $30 Raffles Singapore Sling recipe.

My mom had told me the moon cake recipe story before but I always love listening to her retell it. She’s in her 80s now but when she recalls the stories behind the recipes in her orange notebook, she’s transported to another time and place.

We’re in 1974 Saigon with one recipe. Then we’re in 1975 San Clemente, California, where a kind older woman up the street named Aunt Lucy not only baked American cookies and sweets for us but she also gifted us her recipes. My sisters duly added them to my mom’s orange notebook.

The orange notebook inspired my first cookbook, Into the Vietnamese Kitchen. I wanted to write about how immigrants like my family hold on to food as a means to preserve our heritage. After my book was published in 2006, my mom gifted me the orange notebook, explaining that she no longer needed it. She was keeping recipes in a big recipe box. The notebook is my family heirloom.

If you have recipe books in your family, treasure them.

Related posts on April 30, 1975:

- Revisiting the Fall of Saigon 40 Years later - how my family and others escaped

- Chicken Back and Celery Rice Recipe - a ghetto-ish but luxe dish we made when we first came to America in 1975

- Cooking Vietnamese Food in 1970s America: Things We Were Grateful For - drinking water for one...

- Gratitude Fried Wontons Recipe - we made wontons and threw a party for people who helped us resettle

- Revisiting Saigon Now: Memorable People and Places - what the future holds for Saigon residents now