Has it been a week since the pho video from Bon Appétit magazine went viral for all the wrong reasons? Yes, it has been. During the past seven days, I responded to comments on VWK and social media, taught an Asian dumpling class, and attended a sustainable foods institute. My life has been ultra-rich.

When I wrote the VWK post last Thursday, I didn’t know who would be reading it and how impactful it would be. It was passed around social media and last Friday, an editor at National Public Radio (NPR) invited me to write a commentary on the meaning and potential consequences of the video controversy.

As the Bon Appétit video debacle unfolded, I had communications with people from all kinds of backgrounds and age groups. Some conversations were public while others were private. Given those experiences and articles on food and race politics, such as the ones at the New York Times by Francis Lam, NPR by Maria Godoy and Kat Chow, and Civil Eats by Cathy Erway, I saw an opening.

Below is an excerpt of my comments published on September 13 at NPR:

Pho has a story that’s much longer than a noodle strand. The noodle soup was created at the beginning of the 20th century as genius make-do cooking. French colonials in Vietnam ordered the slaughtering of cows for the steaks they craved. The bones and tough cuts were left to local cooks, who were used to cows as draft animals but soon found a way to turn the leftovers into delicious broth with rice noodles and thinly sliced meat. It was sold as affordable street food that vendors customized for each diner. Pho fans came from all backgrounds, as the soup’s popularity spread — from Hanoi in the north to Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) in the south. Inspiring cooks and even poets, it became Vietnam's national food.

Vietnamese people are nationalistic, and pho is not only part of their cuisine but also their pride. Yes, it was the French who made beef scraps available, and yes, many of the initial pho cooks were Chinese, but the noodle soup was created in Vietnam. The Vietnamese people made the best of their circumstances and turned the situation into something of their own. No one may claim pho but the Vietnamese, whom, as history has proven, are a feisty bunch.

We’ll never know how aware the critics who took Bon Appétit to task were of pho’s history and meaning. As a Vietnamese-American, I wasn’t angered that the chef featured in the video was white; I'm glad that this soup that forms such a rich part of my cultural identity is gaining new fans, and I welcome all into the kitchen to cook it. But, for an authoritative lesson on pho, which is what this video purported to be, why not tap one of the many Vietnamese-American mom-and-pop shops that have long kept this traditional soup simmering around the country? Or, how about letting a Vietnamese-American chef compare notes with the non-Asian chef?

At Mic, a news site with a millennial audience, the controversy was framed as ‘Columbusing’ — a word that describes when white people "discover" something that has been around for years, or even centuries. The term was new to me, but the concept was not. For years, some people conjectured that pho had strong French roots because it resembled feu (“fire” in French), as in pot-au-feu, the boiled beef dinner. The noodle soup's name most likely evolved from the Vietnamese pronunciation of fen, the Chinese term for flat rice noodles. In applying the Columbus metaphor, Mic signaled that pho had truly become part of America's multicultural table. It had become a vehicle for having a difficult, important conversation about race.

This controversy will likely dissipate, like so many things on the Internet. But if there’s anything to be learned from the video fiasco, it's this: Food can — and should — be a way for us to foster deeper understanding of one another.

{The entire commentary is here.}

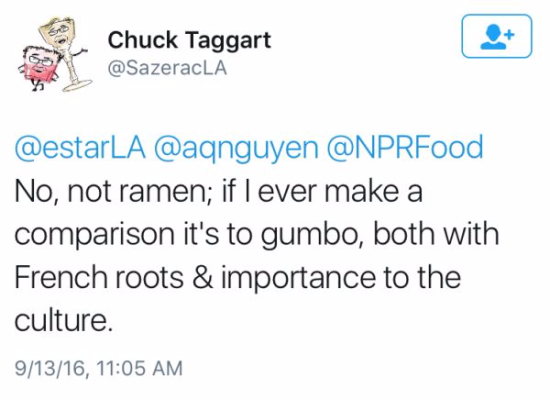

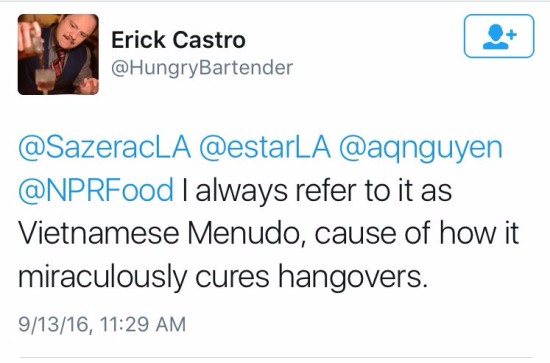

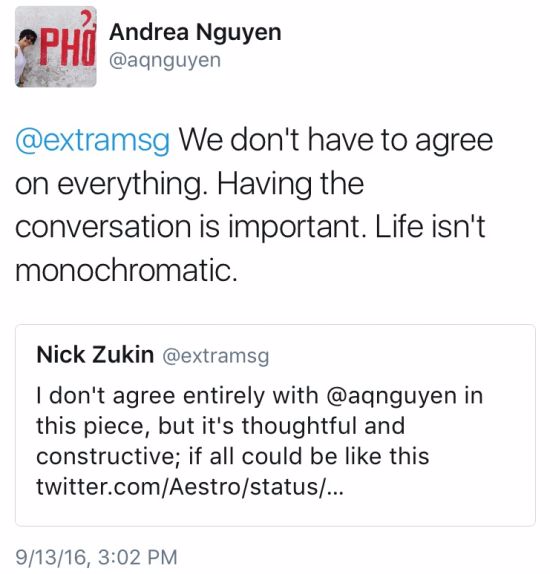

The reactions were great, including these:

Over the weekend on Saturday, Bon Appétit Editor-in-Chief Adam Rappaport issued a second, better-written apology and retitled the post, “About that Pho Video.” After the NPR piece published, the magazine’s online editor emailed to let me know that the discussions here and elsewhere have made them think more critically about how they do things.

Food is a human experience. We all eat, but when there’s context, the food has more flavor.

Related post: Why a Pho Video Boiled Over into Controversy for Bon Appetit Magazine