Where did pho come from? Does pho come from the French word, feu?

Why does pho matter? To help clarify things, here's the introduction

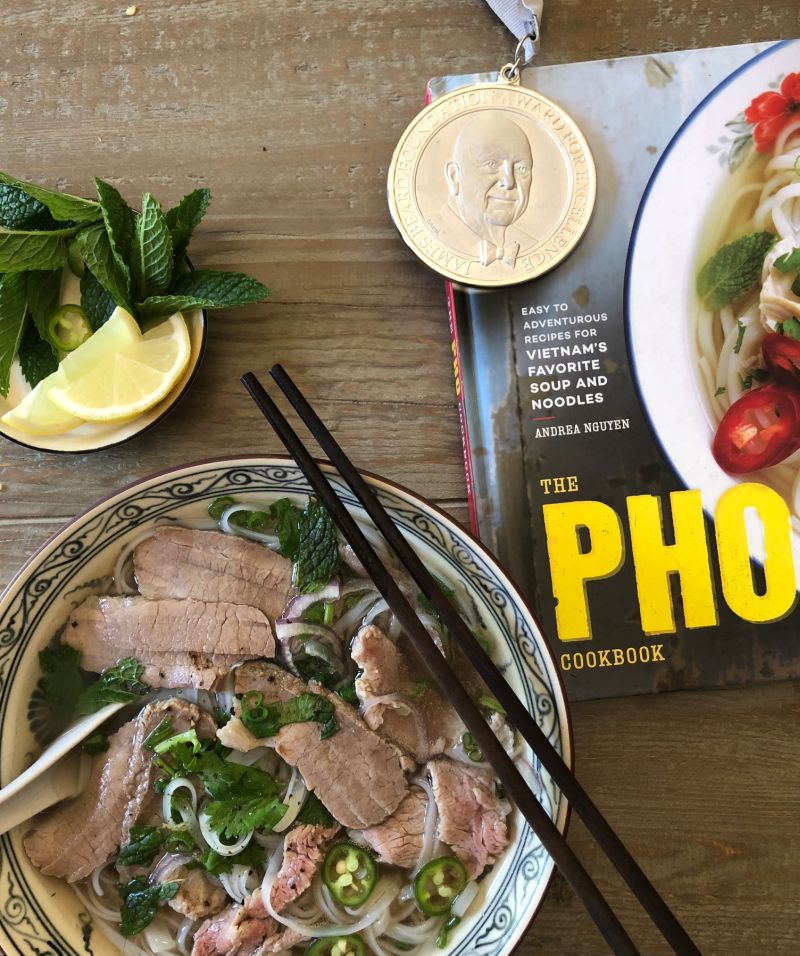

from my James Beard Award-winning book,

The Pho Cookbook (Ten Speed Press, 2017).

Pho is so elemental to Vietnamese culture that people talk about it in terms of romantic relationships. Rice is the dutiful wife that you can rely on, we say. Pho is the flirty mistress that you slip away to visit.

I once asked my parents about this comparison. My dad shook his hips to illustrate the mistress. My mom laughed and quipped, "Pho is fun but you can't have it every day. You would get bored. All things in moderation."

The soup first seduced me in 1974, when I perched on a wooden bench at my parents' favorite pho joint and wielded chopsticks and spoon with dexterity and determination. The shop owners marveled; mom and dad beamed with pride. The fragrant broth, savory beef, and springy rice noodles captivated me as I emptied the bowl. I was five years old and suddenly hooked on soup. That experience is among the most vivid from my childhood in Vietnam.

After we immigrated to the States in 1975, there were no neighborhood pho shops to frequent in San Clemente, California, where my family resettled. My pho forays were often homemade, for Sunday brunch.

Like many Vietnamese expatriates, we began savoring pho as a very special food, a gateway to our cultural roots. My mother regularly brewed beef or chicken pho broth on Saturday, then the next morning after eight o'clock mass, we sped home. Everyone had a job on Mom's pho assembly line.

At the table, our bowls of homemade pho were accompanied by fresh chile slices and a few mint sprigs. The simplicity reflected my parents' upbringing in northern Vietnam, where purity prevailed. They'd lived in liberal Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City) for decades, but they didn't allow embellishments like bean sprouts, Thai basil, or lime wedges. And definitely no sriracha, which Mom deemed un-Vietnamese.

Pho exploration

As a college student in Los Angeles, I went to pho restaurants that served up giant bowls with plates piled high with produce for personalizing flavors. Flummoxed at first, I learned to loosen up, even at the sight of someone squirting hoisin and sriracha into a bowl. Over the years, I practiced making my own pho, developed recipes for my first cookbook, Into the Vietnamese Kitchen (2006), researched pho in Vietnam and wrote articles on it, answered reporter and blogger queries, and taught pho classes to countless cooks.

Interest in pho has risen exponentially as it has moved from the margins to the mainstream. It's a favorite food for many but it's also been the focus of novels, art exhibits, rap songs, and Kickstarter campaigns. People are smitten by Vietnam's signature dish for many reasons: Pho is comforting (noodles in clear broth satisfy), healthy (there's little fat and gluten), restorative (try it for colds and hangovers), and friendly (you can have it your way). It's also delicious.

I figured that I knew what pho was all about until friends, Facebook fans, and then my publisher suggested that I write a pho cookbook. Seriously? What was there to present beyond the familiar brothy bowl? As it turned out, a lot. It didn't take me long to realize that the world of pho was unusually rich with culinary and cultural gems.

Original pho

Vietnam is a country with a history spanning over thirty-five hundred years, but pho is a relatively new food. It's unclear how and when it was birthed, though most people agree that the magical moment happened at the beginning of the twentieth century in and near Hanoi, the capital located in the northern part of the country.

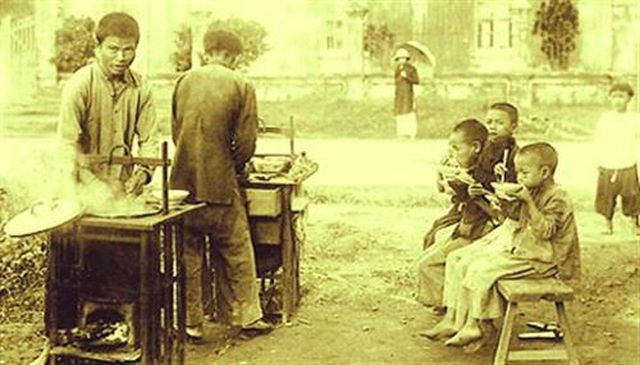

Prior to 1910, images of pho street food vendors appeared in Technique du Peuple Annamite (Mechanics and Crafts of the People of Annam, 1908-1910), a multivolume effort by Henri J. Oger. He was a colonial administrator who commissioned artisans and wood carvers to document life in Hanoi and the surrounding countryside.

But what was the source of the original pho?

Some say that long before pho got popularized, it was being prepared in Van Cu, an impoverished village in Nam Dinh Province located about sixty miles (one hundred kilometers) southeast of Hanoi. The village and province produced generations of pho masters, many of whom relocated to the capital to open well-regarded pho shops.

We'll likely never know for certain how pho first came about, but it's in great company: almost all beloved foods have origin controversies that fuel conversations and imaginations. What's clear is that pho was created from cultures rubbing shoulders.

There are many theories, but a reasonable explanation for pho was presented in "100 Năm Phở Việt" ("100 Years of Vietnamese Pho," 2010), an oft-cited historical essay by Dung Quang Trinh. In the Hanoi area during the early 1900s, there was a lot of interaction between the Vietnamese, French, and Chinese (China and Vietnam are next-door neighbors). The French, who officially occupied Vietnam from the 1880s to 1954, satiated their desires for tender steaks by slaughtering cows, which the Vietnamese traditionally used as draft animals. The leftover bones and scraps were salvaged and sold by a handful of Hanoi butchers.

Locals hadn't yet developed a taste for beef, and the butchers had to promote it via special deals and sales. Street vendors who were already selling noodle soup recognized an opportunity to offer something new. It was just a matter of switching the menu of their portable kitchens.

At that time, a noodle soup called xáo trâu was very popular. It was simply made, with slices of water buffalo meat cooked in broth with rice vermicelli. The vendors swapped beef for water buffalo. Somewhere in the process, they also traded flat rice noodles for the round rice vermicelli.

The result was a noodle soup that some people called xáo bò, but since many of the vendors were Chinese, the Vietnamese-Cantonese name prevailed: ngưu nhục phấn (beef with rice noodles). Viet culture and language were in flux when pho emerged on the scene.

The new noodle soup was often prepared and sold by food hawkers who roamed the streets looking for customers. Many of the initial pho customers were Chinese coolies and other workers whose livelihoods were tied to the French and Chinese merchant ships that sailed up and down the Red River; the river flowed from Yunnan Province, past the edge of Hanoi, then into the Gulf of Tonkin, connecting a diverse group of people.

French and Chinese merchant ships employed many Yunnanese, who likely identified ngưu nhục phấn as being akin to Yunnan's guò qiáo mǐ xiàn (crossing the bridge noodles), composed of rice noodles, superhot broth, meat, and vegetables. The beef noodle soup caught on with the Chinese workers and, soon thereafter, with the many ethnic Vietnamese who began working on the river, too.

The popularity of the dish spread as the number of street food vendors rose in response to Hanoi's colonial urbanization, according to historian Erica Peters. The initial pho shops opened in the bustling Old Quarter (the main commercial hub) and more followed. Nam Dinh-style pho shops seeded their reputation around 1925, when a skilled cook from Van Cu opened a storefront in Hanoi. By 1930, pho could be found in many parts of the city.

How did ngưu nhục phấn become phở?

It is likely that as the dish caught on, street hawkers became more competitive and abbreviated their distinctive calls. For example, “Ngưu nhục phấn đây” (Beef and rice noodles here) was shortened to “Ngưu phấn a” then “Phấn a” or “Phốn ơ” and finally settled into one word, phở. It's been suggested that phở won because if phấn is mispronounced or misheard as phân, it would mean "excrement."

In a Vietnamese language dictionary published around 1930, an entry for phở defined it as a dish of narrowly sliced noodles and beef, its name having been derived from phấn, the Viet pronunciation of fěn, the Chinese term for flat rice noodle. Despite the Viet-Chinese definition, some people have conjectured that the term is French in origin because its pronunciation bears a resemblance to feu ("fire" in French), as in pot-au-feu, the boiled beef dinner. The terms indeed sound similar, and pho came about during the French colonial period, but it's difficult to accept that the soup directly descended from French cuisine. Pho doesn't involve lots of vegetables like pot-au-feu does, for example. A plausible Franco-Viet connection is the technique of charring ginger and onion or shallot for pho broth.

No one may claim pho but the Vietnamese because it happened on Vietnamese soil under a unique set of circumstances. It was genius make-do cooking. While original pho was a simple bowl of broth, noodles, and boiled beef, as time went on, cooks began experimenting with different techniques and ingredients, some of which were influenced by other cultures and others that were spurred on by necessity.

In the late 1920s, people debated the merits of pho featuring spices similar to those in Chinese five-spice powder, peanut oil, tofu, and cà cuống (a pear-scented water beetle pheromone). Vendors were serving up pho with rare beef slices by 1930. Around that time, phở xào dòn, panfried pho rice noodles topped with a saucy beef and vegetable stir-fry, was introduced and well received; see recipes in the Pho Cookbook chapter on stir-fried, panfried, and deep-fried pho dishes.

Things got heated in 1939 when pho restaurants began selling chicken pho (phở gà). It usually happened on Mondays and Fridays and was likely due to the government forbidding the sale of beef on those days in order to control the slaughtering of draft animals for food. Purists initially decried chicken pho as being un-pho-like, but in the end, it prevailed as a worthy and tasty preparation in its own right. In fact, some pho shops decided to specialize in phở gà.

One last note about pho terminology

Phở not only refers to the noodle soup, but is also shorthand for the dish’s flat rice noodles, bánh phở. The word’s dual culinary meanings are telling. Pho is not only about the soup, but also about the rice noodle and its many glorious manifestations.

Protest and political pho

Foreign occupation, civil war, the Vietnam War, reunification, and rebuilding -- the twentieth century was tumultuous for Vietnam. Pho got swept up in the events that unfolded.

During the 1930s, many authors and poets in Hanoi resisted the French occupation with their pens. In 1934, one of the country's distinguished poets, Tu Mo, published “Phở” Đức Tụng (An Ode to Pho). A nationalistic satirist, Tu Mo wanted to convey Viet pride and people's desire for justice and self-determination. After espousing the unique deliciousness of pho, how it arouses the senses, and how its bone broth nourishes rich and poor as well as artists, singers, and prostitutes, he concluded with these lines, which I have loosely translated:

Don't downgrade pho by labeling it a humble food,

excerpted from Tu Mo's “Phở” Đức Tụng (An Ode to Pho)

Even the city of Paris has to welcome pho.

Compared to other international foods of note,

It is delicious yet inexpensive and is often crowned the best.

Living in this world without eating pho is foolish,

Upon death, the altar offerings should include it.

Now go savor pho, or you shall crave it.

When the French colonial period ended in 1954 and the Geneva Accords split the country into North and South Vietnam, about one million northerners migrated southward, heralding the arrival of Hanoi-style pho to Saigon. Saigonese were familiar with pho by 1950, but proud northerners like my mother say that pho wasn't popularized there until they showed up. (Restaurants abroad named "Pho 1954" often give a nod to that important marker in Vietnamese history and cuisine.)

In the agriculturally rich and freewheeling south, pho broth eventually developed a sweet edge, as cooks added a touch of Chinese rock sugar. Southerners also liked a lot of accessories: bean sprouts, Thai basil, chile sauce, and a hoisin-like fermented bean sauce. Northerners were aghast. The new additions desecrated their well-balanced, delicate soup. To this day, the regional pho fight between Hanoi and Saigon -- north versus south, salty versus sweet, simple versus eclectic -- rages on.

The late 1950s were cruel to pho in Hanoi. The Communist Party nationalized many businesses for the sake of social reform. The Soviet Union sent economic aid, including a lot of potato starch and wheat flour. Xuan Phuong, a former party loyalist, recounted that era's pho experience in her compelling 2004 memoir, Ao Dai: My War, My Country, My Vietnam.

The government restricted "real" pho because it wasted precious rice, she explained, and the resulting state-run pho shops produced bowls of "rotten rice noodles, a little bit of tough meat, and a tasteless broth." People who could afford pho lined up for it nevertheless, only to face unhygienic conditions (chopsticks were seldom washed) and suffer humiliation (holes were pierced in spoons to prevent people from stealing them). Pho street vendors were limited to selling soup with potato starch noodles. Hanoians determined to get good pho found a work-around, as she described:

Little by little, the rules were overlooked. To deceive controllers, the street merchants placed a small basket of those shriveled up noodles on display. But the pho, the real stuff, was underneath. It was almost as good as it had used to be and hardly more expensive than the substitute. We all passed on our list of secret addresses. “I would like a bowl of soup with potato flour noodles,†we would say out loud, just in case any State officials were hanging around. The merchant would understand immediately. But then the pho had to be downed very quickly to keep the unfortunate man or woman from having his or her equipment seized, as well as a fine to pay.

Source: Ao Dai: My War, My Country, My Vietnam by Xuan Huong

Wartime pho

During the Vietnam War, a different kind of pho underground operated in Saigon. Starting around 1965, a Viet Cong spy cell operated out of Pho Binh (literally "Peace Noodles"). The seven-table joint was a communist nerve center for carrying out the city's part in the 1968 Tet Offensive. According to a 2010 Los Angeles Times article, Pho Binh was a hub for organizing and transporting weapons from northern strongholds to secret hiding places in Saigon.

Elsewhere in the city, people tried to maintain calm and normal lives. Many headed to "pho streets" such as Ly Thai To and Pasteur for satisfying bowls at popular restaurants like Pho Hoa and Pho Tau Bay.

In Hanoi, wartime scarcity forced state-run pho shops to make the soup without meat. In 1964, after the United States began sending unmanned reconnaissance planes to photograph North Vietnam, locals mockingly called their meager soup phở không người lái, literally "pho without a pilot." A bowl of pho noodle soup is defined by its protein (you order pho by the cuts of beef or chicken), and meatless pho seemed as surreal, if not as absurd, as a drone aircraft. Wartime pho in Hanoi was often served inappropriately, namely with leftover cold rice and baguette. Fried breadsticks called bánh quẩy were the saving grace; they were procured from Chinese vendors who spotted an opportunity to inject richness into an otherwise sad pho experience. The breadsticks became a local pho accompaniment that endures today in the capital.

My cousin Huy Do Le, a Hanoi native in his late fifties, recalled the state-run pho shops producing deplorable soup, whereas street pho operators were much better. He and a friend, poet Giang Van, lived through those hard times, as well as the lean years after the Vietnam War ended in 1975. The nation was reunified as one, but its economy was in shambles. Food was rationed and people stood in line for nearly everything, including pho. One midmorning over tea, they wistfully discussed their longing for the elegant simplicity of Hanoi foodways: smallish portions of flat rice noodles, savory yet slightly sweet broth, and sliced cooked beef. "No fried breadsticks, condiments, or other extra things. Traditional Hanoi style is pure and delicate," Giang Van said.

Saigonese continue to celebrate pho with all of the embellishments because that's how they like it. For people who experienced extra hardship, there's a smidgen of defiance, too. During a pho breakfast in Saigon, I asked my cousin Phu Si Nguyen, an energetic retired teacher in his seventies, about pho after the Communist takeover in April 1975. "My brother and I were jailed, sent to reeducation camps," he said with a wry smile. "Times were difficult, but now, there is plenty of good pho in Saigon." We all nodded, added bean sprouts and herbs to our bowls, and dug in.

Culinary and cultural pho

Pho is about tradition as much as it is about change. It comforts as well as stokes the imagination.

While beef pho remains the favorite and chicken pho ranks second in terms of popularity, Vietnamese cooks are always coming up with something new. Some dishes, like pho with beef stewed in white wine (phở sốt vang) and sour pho (phở chua), never totally caught on, whereas fresh pho noodle rolls were a hit.

As interest in Vietnamese food and travel rises, there's incredible excitement about pho. In Hanoi, family-owned, multigenerational pho shops do a brisk business with traditionalists, while young people are keen on nontraditional preparations such as Chicken Pho Noodle Salad and Deep-Fried Pho Noodles. Souvenir vendors in the historic Old Quarter sell pho T-shirts and postcards. Tourists and street food tours include pho on their bucket lists. The esteemed Hotel Sofitel Legend Metropole has a pho cocktail on its menu.

In Saigon, where there are pho concerns large and small, happy customers slurp away morning, noon, and night. Tourists flock to Pho 2000, where former president Bill Clinton ate, while locals patronize favorites such as Pho Le and Pho Hoa. Arty and modern Ru Pho Bar presents pho made with brown rice noodles. Customers at Pho Hai Thien may order pho with a rainbow of noodles tinted by vegetable juices. Pho tchotchkes are sold on the streets as well as at the airport.

Outside of the motherland, pho has taken root wherever there are Vietnamese people. Its strongholds include North America, France, and Australia, where many immigrants have settled and built thriving Little Saigon enclaves. Whether they were born in Vietnam or abroad, people of Viet ancestry are reinforcing their cultural roots through pho, opening and patronizing small joints in their communities, cooking up their own at home, and introducing the noodle soup to friends. Nowadays, Viet-owned restaurants present traditional broths and freshly made bánh phở noodles, but also try out new ideas, such as crawfish pho, sous vide-beef pho, and pho fried rice.

Mainstream supermarkets in the United States carry pho kits and instant pho bowls. Non-Vietnamese chefs are serving pho in restaurants while home cooks try their hands at making it themselves. The widespread availability of fish sauce and rice noodles at supermarkets, ethnic grocers, and online makes DIY pho doable.

The future of pho shines very bright. Let's get started with making some.

Source: The Pho Cookbook by Andrea Nguyen. No reprinting or re-posting without permission.

Feng Cheng says

Obviously the name pho is from Chinese “Fen 粉”, like you can see “Guilin rice noodle 桂林米粉 “ restaurant chains everywhere across China. Guilin in Southwest of China, where its province borders to Vietnam. Even in a picture of this article, there is 粉 fen in Chinese beside the man carrying a pole of noodle

Andrea Nguyen says

Indeed, the terms are very related!!! Many people still think that pho came from the French term, feu. If only they read Chinese! Thanks for noticing. =D

Bí Bếp says

The noodles or fun would not made up to pho but the essence of pho... would be the... beef broth, which there is there is nothing in Chinese cuisine could connect to it.

Andrea Nguyen says

With all due respects, I beg to differ. Dishes like pho cuon are about the noodle, banh pho. Pho Xao is about the noodle. A dual meaning is how I interpret it. The first pho cooks were Chinese in heritage. Interaction between people of different cultures is a natural part of Vietnamese history. Pho is Vietnamese but it's important that it was born from cultures rubbing shoulders, interacting. That's human. That's cooking.

Jacki says

Yes there is, there is a Taiwanese Braised Beef Noodle soup with Chinese origins which has the beef broth with star anise, cinnamon...very similar in taste.