Even though the Soviet Union and North Vietnam were closely aligned during the twentieth century, Russian’s imprint on Viet popular culture is shallow. I grew up with a beet, potato and carrot salad called rau củ trộn (aka salade Russe), introduced to Vietnam by the French. My north Vietnamese cousins were educated in the USSR, and I’ve noted Russian tourists on Phu Quoc island. But honestly, I know very little about Russian culture and food, but realize its ties to Asia.

Cue Darra Goldstein’s new book, Beyond the North Wind. It's loaded with interesting recipes beyond borscht, facts and perspectives that only Darra — a prominent Russian scholar, emerita professor of Williams College, founding editor of Gastronomica and former Stoli vodka girl — could generously and expertly provide with giddy enthusiasm.

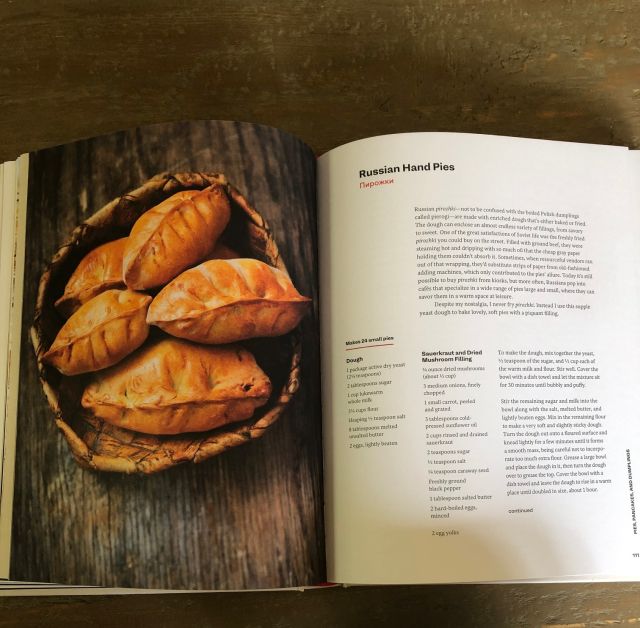

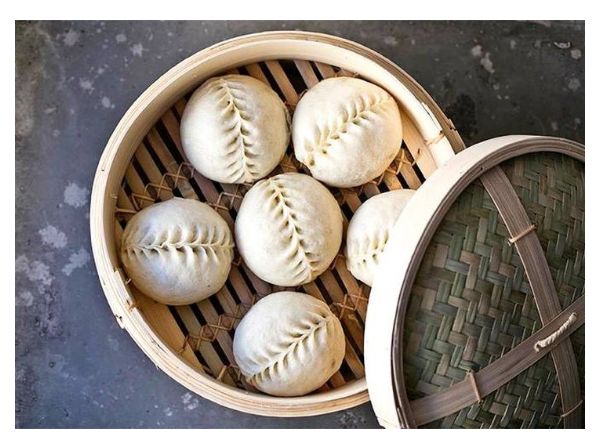

She’s obviously not stodgy. For those reasons, I was happy to let Darra’s new book school me on Russian foodways. Coincidentally, the first page I opened to was for Russian Hand Pies (page 111). I was struck by the pleating. They looked just like steamed bao that I’d seen at a Korean market! I noodled around and found out that Koreans living in Russia are called Koreo-saram.

Koreo-saram / Russian-Korean Food

What is Koreo-saram food like? Did Darra have experience with it? I asked and she responded:

The history of Korean settlement in the former USSR is really interesting (and painful). During the Soviet years, the group that had the most presence in the Moscow farmer’s markets was from Uzbekistan. Uzbek Koreo-saram always had stalls in the pickled/fermented foods aisles, and their specialty was a spicy shredded carrot salad, which became nearly a staple on Russian tables, it was so beloved. It’s still popular — I recently saw some at a market in Murmansk, far above the Arctic Circle. It’s very simple to make — you just add onions sautéed in vegetable oil and raw minced garlic (lots of it) to shredded carrots and then mix in salt, pepper, cayenne, and a little sugar or honey. Some people add ground coriander. What makes is so appealing apart from the taste is its brilliant orange color.

Korean food is very trendy in Russia now. What’s interesting it how tied up it is with traumatic history. Moscow is finally getting some restaurants that reflect Korean food as eaten in Korea, but until recently what Russians ate was largely the food of the Korean diaspora in the Far East and Central Asia. The carrot salad originated in the 1930s, when Koreans living in the Russian Far East were deported to Central Asia by Stalin. They created it to make a kind of banchan with ingredients that were readily available.

There’s now a chain of street food kiosks in Moscow that specializes in pyanse, which were introduced by Koreans living on Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East (the Koreans were forcibly settled there by the Japanese in the early 20th century). Pyanse became really popular among the local population, and they eventually spread throughout the country. I read that when pyanse were first introduced to Moscow, the Russians asked “When will they turn brown?,” expecting them to be like golden baked pirozhki. They usually have a meat and cabbage filling, not unlike pirozhki, except that the spices are different and of course they’re steamed.

The pyanse photo above is from this article that Darra pointed to. There are more photos to check out. You don't have to read Russian to understand the gist of its popularity.

Creating Russian-Korean Hand Pie Filling

Intrigued, I became emboldened by Darra's recipe headnote (introduction) for Russian hand pies:

Russian pirozhki—not to be confused with the boiled Polish dumplings called pierogi—are made with enriched dough that’s either baked or fried. The dough can enclose an almost endless variety of fillings, from savory to sweet. One of the great satisfactions of Soviet life was the freshly fried pirozhki you could buy on the street. Filled with ground beef, they were steaming hot and dripping with so much oil that the cheap gray paper holding them couldn’t absorb it. Sometimes, when resourceful vendors ran out of that wrapping, they’d substitute strips of paper from old-fashioned adding machines, which only contributed to the pies’ allure. Today it’s still possible to buy pirozhki from kiosks, but more often, Russians pop into cafés that specialize in a wide range of pies large and small, where they can savor them in a warm space at leisure.

The second sentence, which I set in bold, combined with Darra’s insights into Koreo-saram food, opened the door for me to riff on her recipe. I made two fillings—her original filling of sauerkraut and mushroom and a Koreo-saram inspired filling of kimchi and shiitake.

It wasn’t a far-fetched idea since all I had to do was use mild-flavored Korean baek (white) kimchi, which is made without red pepper flakes, instead of sauerkraut. The dried shiitake was an easy swap for porcini. Korean cooking employs a lot of the onion family so I kept that.

There was already carrot in the Sinto brand of kimchi I’d purchased so it was copacetic with the Russian filling; I simply was adding more carrot to color up the Korean filling. In the photo below, the Koreo-saram filling is at top, and the Russian filling at bottom.

Instead of caraway’s sweet note, you’ll see in the recipe, that I season with gochugaru, Korean red pepper flakes. The Russian filling gets finished with butter so I swapped sesame oil. The substitutions were seamless and both fillings tasted great, like close kin.

Dough, Shaping and Other Tips

Darra’s recipe forewarns you that the dough is sticky. I found that to be true and found an easy workaround. I don’t know if I got the shape 100 percent right but the hand pies baked up just fine. Here’s a little video I made:

Each batch makes twenty four pies. I had hungry neighbors, including two young men who’d never eaten Russian food before. A dozen of the Russian and Russian-Korean hand pies disappeared in a flash.

These hand pies store and reheat well too. Refrigerate baked ones or freeze them and thaw. Reheat in a preheated 350F toaster or regular oven until the pies are hot.

I didn’t know much about Russian cooking before opening Darra’s book. Now I’m looking forward to diving in further.

More Recipes for Little Pies!

Russian Hand Pies Recipe

Ingredients

Pie Dough

- 1 package active dry yeast (2 ¼ teaspoons)

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 1 cup lukewarm whole milk

- 3 ¼ cups 16.25 oz all-purpose flour, unbleached or bleached

- Heaping ½ teaspoon fine sea salt

- 8 tablespoons 1 stick melted unsalted butter

- 2 eggs, lightly beaten

Filling and Glaze

- ¼ ounce dried porcini or shiitake mushroom (about ⅓ cup)

- 3 medium onions finely chopped

- 1 small carrot peeled and grated on the largest hole of a grater

- 3 tablespoons cold-pressed sunflower oil

- 2 cups rinsed and drained sauerkraut or finely chopped drained kimchi

- 2 teaspoons sugar

- ½ teaspoon salt

- ¼ teaspoon caraway seed, or 1 teaspoon gochugaru (Korean red pepper flakes)

- Freshly ground black pepper

- 1 tablespoon salted butter or toasted sesame oil (if using kimchi)

- 2 hard-boiled eggs, finely chopped

- 2 egg yolks, for glazing

Instructions

- To make the dough, mix together the yeast, 1⁄2 teaspoon of the sugar, and 1⁄2 cup each of the warm milk and flour. Stir well. Cover the bowl with a dish towel and let the mixture sit for 30 minutes until bubbly and puffy.

- Stir the remaining sugar and milk into the bowl along with the salt, melted butter, and lightly beaten eggs. Mix in the remaining flour to make a very soft and slightly sticky dough. Let the dough sit, uncovered, for 5 minutes to hydrate and become easier to work.

- Turn the dough out onto a well-floured surface (use about 1 to 2 tablespoons flour) and knead lightly for a few minutes until it forms a smooth mass, being careful not to incorporate too much extra flour. Grease a large bowl and place the dough in it, then turn the dough over to grease the top. Cover the bowl with a dish towel and leave the dough to rise in a warm place until doubled in size, about 1 hour.

- While the dough is rising, make the filling. Soak the mushrooms in warm water for 30 minutes to soften. In a large skillet, sauté the onions and carrot in the oil until softened, 8 to 10 minutes. Drain the mushrooms and chop them finely. (You should have about ¼ cup.) Add the mushrooms to the onion mixture along with the sauerkraut (or kimchi), sugar, salt, caraway (or gochugaru), and plenty of pepper. Cook, covered, over low heat for 10 minutes. Stir in the butter and the minced hard-boiled eggs. Remove the pan from the heat.

- Line two large baking sheets with parchment paper. Punch down the risen dough and divide it into four pieces. (Each piece will weigh about 8 ounces; keep them separated with parchment to avoid sticking.) Work with one piece at a time; leave the others in the bowl, covered with the dish towel, so that they don’t dry out. Divide each quarter of dough into six equal pieces. On a lightly floured surface, roll or pat out the pieces of dough into 3 ½-inch rounds.

- Place 2 tablespoons of the filling in the center of each round, then bring the two sides of the dough together at the top. Starting at one end of the pie, pinch the edges together between your thumb and forefinger. To make decorative pleats, bring the lower edge of the dough up and press it into the inside of the adjacent dough. Make another pinch and press the dough down into the adjacent lower edge. Move back and forth along the pie in this manner to make a decorative, tightly sealed seam. Once all the pies are sealed and shaped, cover them with a dish towel and allow to rise for 20 minutes. (Watch the video in the main post, if you need an assist!)

- While the pies are rising, preheat the oven to 350°F. Stir the egg yolks together in a small bowl and brush the pies all over with this glaze. Check the seal on each pie and pinch any open areas. Bake the pies for 20 minutes, until golden, and serve hot.

Darra Goldstein says

Andrea, I LOVE this post!! I can’t wait to get home and try your Korean riff on these pies. Thank you, as always, for inspiring us with your creativity.

Elizabeth Andoh says

What a WONDERFUL collaboration of ideas and foods! Love it!

Katrin Lausch says

This is utterly inspiring. I did not know about koreo-saram food before I read your post. Now I want to find out more about it and I will also try your recipe. Thank you for sharing, regards from Germany.

Andrea Nguyen says

My pleasure, Katrin!

Sandy says

When we were in Nha Trang a few years ago, many of the restaurant menus also had Russian. The hotel staff mentioned that Nha Trang was a popular vacation spot for Russians.

Andrea Nguyen says

Fascinating! Thanks for sharing your Viet-Russian experience!

rinshin says

Very interesting. Fried piroshki is also very popular in Japan. We dip into mustard to eat. You can sometimes find them at Nijiya Market freshly made in Mountain View. They alternate between fried curried pan/bread.

Andrea Nguyen says

That's very interesting, Rinshin! I'll look for them at Nijiya.

Masha says

As a Ukrainian-American, I'd always wondered about dishes like Korean carrots and talked with a lot of Korean friends about similarities in some of our dishes! So cool and exciting to hear about the history of our people interacting, even though it's under painful circumstances. Thanks for the illuminating article, I've been thinking about this for days.

Andrea Nguyen says

Masha, thank you so much for commenting! People don't cook an eat in silos anymore. The beauty of the internet is we can compare experiences and compare notes. I'm so happy you weighed in!