Last week, my first article publish in the New York Times! The story was about my nearly 40-year obsession with mapo tofu. I also included three recipes to illustrate mapo's roots and potential. As a follow-up to the article, I’m elaborating on doubanjiang — a key ingredient for preparing Sichuan favorites.

If you’ve never heard of doubanjiang (“doh-bahn-gee-and“, also called douban), it’s a spicy, umami-laden fermented seasoning that's primarily made of chile and broad (fava) beans, though soybeans may be used instead of or in combination with the broad beans.

Doubanjiang ranges in color, from bright red to mature mahogany. It also varies in texture, from saucy and pasty to oily pasty. Doubanjiang is the coarse stuff in the above photo, photographed in 2010 by my friend Karen Shinto when we visited Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province in China. I was on my Asian tofu expedition, and Chengdu, the home of mapo tofu, was on my hit list.

Doubanjiang in the Making

To help me better understand mapo tofu, widely respected Sichuan chef Yu Bo, of Yu's Family Kitchen, took us to visit a producer in Pixian, a suburb of Chengdu. Many contend that Pixian produces the best doubanjiang. We checked out the paste in various stages of maturation; the better pastes age for years. The paste in each large planter-size container below is routinely hand-stirred, sometimes with a plastic spoon, wooden paddle, or bamboo pole. It's dense, so the work is tedious and difficult.

I couldn’t bring any doubanjiang back to the U.S. on that trip, which is fine because it’s better to develop recipes with Stateside ingredients. Ten years ago, Pixian doubanjiang was emerging at certain Chinese markets. It wasn’t easy to source because Sichuan cooking and mapo tofu weren't as popular with mainstream eaters and cooks.

Good options exist today, but if you’re new to doubanjiang, sourcing and selecting it may be confusing. This post will hopefully help. I wrote about doubanjiang years ago, but the choices have changed for the better!

Three Main Contenders

Unless you're fluent in reading Chinese, it's confusing to buy an ingredient like doubanjiang. I purchased three kinds, and none of them are clearly labeled as doubanjiang in Romanized language.

So, remember that it may be spelled as "toban djan" or it may labeled as broad bean sauce, broad bean chili sauce, or fermented chili bean paste/sauce. Squint and you may see doubanjiang somewhere on the label. I prefer to translate doubanjiang as fermented chile bean sauce/paste because chiles are more plentiful in the mixture than beans.

I purchased two kinds by Lee Kum Lee ("LKK") because it's a leading Chinese condiment brand that you'll find at Asian markets. Here's how they fair against the one on the right from Pixian.

Toban Djan

This is a funny spelling of doubanjiang that's used by Lee Kum Kee, a well-distributed producer of Asian condiments. Based in Hong Kong with U.S. offices in America, their products cover mostly southern China.

In general, LKK products are great for entry-level cooking because they're friendly, balanced, and accessible. How does LKK, a Cantonese maker of sauces, convey doubanjiang, which some describe as the "soul of Sichuan"?

Well, it's gotten a lot better. Ten years ago, LKK's toban djan tasted mild and weak. I had to use extra in my mapo tofu recipe, and it threw things off. Perhaps with the rise of Sichuan cooking, Lee Kum Kee got bolder and changed its formulation. Their version, then as now, contains both fermented soybeans and broad beans among the ingredients used.

At the time of this writing, the LKK sauce is more robust than before, though it's not as fermented, earthy, and fiery as other versions (keep reading below!). Toban djan cooks up into a brighter red than its more fermented kin. Compared to before, I'm much happier using it and would recommend it. For many cooks, Lee Kum Kee's toban djan is their go-to. It's passable by Fuchsia Dunlop standards. (Note that Amoy brand, popular in Hong Kong, labels theirs as "Toban Sauce".)

Doubanjiang with Chile Oil

If you enjoy big heat, seek doubanjiang with chile oil. I bought Lee Kum Kee's Sichuan-style broad bean sauce, because it was readily available. Since LKK products tend toward being mild-flavored and made for a gentle Cantonese palate, I thought the red oil (红油) would be fragrant and moderately hot. So, I put extra doubanjiang into my mapo and paid the price. It was just hot, not perfumey and complex. Someone on Twitter said she combined it with LKK's toban djan.

According to Fuchsia Dunlop in her excellent The Food of Sichuan (an updated version of Land of Plenty), many Chinese chefs use the oily version because it imparts a strong red color. However, it's seen as less authentic than the traditional oil-free version.

Lee Kum Kee also sells douban made with dried shrimp; oil is among the ingredients listed but unclear how oily the condiment is. If you want bling and heat, go for oily doubanjiang! If the store sells a brand other than LKK, try it to broaden your douban horizons.

Pixian Doubanjiang

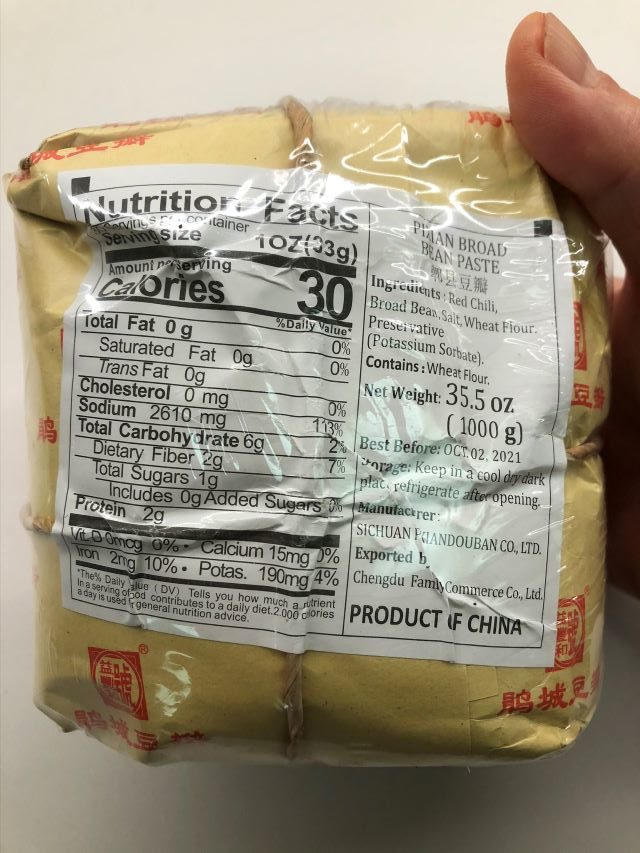

Doubanjiang is made in many places and in a variety of styles, but for Sichuan food connoisseurs, the version made in Pixian is often touted as the best. To find Pixian doubanjiang at a Chinese market, head to the condiment aisle and look high and low for packages of somewhat mysterious looking, squishy paper cubes tied with string and sealed up in plastic. It's legit doubanjiang made in Pixian, though you wouldn't know it unless you read Chinese.

In fact, check the front of the label and notice these characters: 郫县豆瓣. According to Chris Liang of MalaFood.com, which has excellent information on how Pixian doubanjiang is made, those characters indicate official government verification of authenticity. It's like D.O.C. denominations of origin.

The above Pixian doubanjiang is the most widely distributed one in the States. Turns out it's made by Juan Cheng, a brand belonging to a Chinese government-owned company named Sichuan Pixian Douban Corporation, what you'll notice on the label. The label also says this is a China Time-Honored Brand — something that I used to chuckle at. Turns out that honorific phrase carries official weight, according to Taylor Holiday of Mala Market, a purveyor of Sichuan ingredients.

Ingredient wise, Juan Cheng's Pixian doubanjiang has a preservative. However, its ingredient list is much shorter than that of Lee Kum Kee's and other brands.

I've been buying the brand for years. A kilo of doubanjiang is a commitment, but know that it keeps indefinitely in the fridge. I store it in a repurposed mayo jar.

Juan Cheng is currently a leading brand of pixian doubanjiang. I prefer the coarse, old timey paste, which is sold at a convenient but high price at Amazon; at an Asian market, it's roughly $6 per kilo. Juan Cheng also has an oily version sold in jars, which you may purchase online too.

Mala Market sells a 3-year old Pixian doubanjiang by Juan Cheng that I'm eager to try. This one looks promising too!

Underdog Doubanjiang from Sichuan, Taiwan, and Japan

Other than Cantonese and Pixian doubanjiang, there are Sichuan brands to try. For example, look for Youjoy via sites such as Post Sharp Store, an Asian-American vendor with a retail operation in Quincy, Massachusetts.

There's also Taiwanese doubanjiang too! Over the years, I've tried mild and tasty Ming Teh brand, which is sold at some Chinese markets; I've found it at Ranch 99. Compared with the Sichuan and Cantonese versions, Ming Teh's renditions are not as hot, but they have deep umami flavor. It's a good brand with roots in Sichuan. Ming Teh doubanjiang comes in a spicy version with chile oil, spicy with spices, and a mild version without chile. You don't have to have fiery mapo tofu all the time!

There's also Taiwanese canned doubanjiang, labeled as Szechuan hot bean sauce (the company also makes Szechuan bean sauce, which is not spicy). It may be shelved with canned vegetables instead of jarred condiments. The cans come in small sizes (think the diminutive cans of sliced olives) and large ones (soup can size). Try the small one if you're new to it.

I just noticed a Japanese version of doubanjiang by Yuki. Because or the Japanese palate, it's likely on the mild side compared to the Sichuan versions. If you've tried it, let me know your thoughts.

Final Doubanjiang Shopping Tips

When shopping, remember these characters for douban and you'll discover many kinds:

豆瓣

Producers may present the characters left to right, right to left, or high to low. Try different kinds to gauge a heat, salty, sweet, and fatty flavor profile that you like. Some are coarser than others, too.

No matter what brand you get, you can't really go wrong because you can tweak the flavors with sugar (tame heat), salt (add umami), or water (mellow intensity). What's important is getting to an Asian market to explore what they carry!

Related Links

- Mapo Tofu Lasagna

- My Best Mapo Tofu

- Vegetarian Mapo Tofu

- Instant Pot Sichuan Beef Noodle Soup

- Spicy Beef and Tofu Skin Noodle Soup

- What I Learned from Loving Mapo Tofu (at NYT, with recipes for traditional Mapo Tofu, Mapo Tofu Spaghetti and Mapo Nachos)

- Mala Foods -- great for geeky details on Sichuan ingredients

- Mala Market -- a Stateside importer of quality Sichuan ingredients

David says

Here in Sydney, Australia, we are blessed with very many good Asian food stores. Ive been using a LKK Douban Sauce but it is labelled differently to the one that is mentioned above. It is called Sichuan Chilli Douban Sauce, on the list of ingredients it has 30% Pixian Douban and broadbeans amongst over ingredients. After reading this article, I'm going to see if I can try some others as there are a few other brands to choose from in the stores. Thanks for the great information!

Andrea Nguyen says

I've only been to the Viet shops in Cabramatta, and they were great! It sounds like you got the oily LKK douban. I can't imagine Sydney not having Pixian DBJ options. Good luck on your fiery hunt!

Cynthia says

Thank you! I had assumed these all contain soy (I’m allergic). This might be a good sub for fermented sauces I know I can’t have. Your insight on alternative uses of ingredients is always appreciated. Even if not authentic, something that’s evocative that I can have really expands my horizons.

Andrea Nguyen says

No, there are non-soy options. Wheat is major obstacle, but I think the amount is smallish. That said, the Japanese brand is GF.

Great idea on using DBJ as a sub for soy-based sauces!

Rachel Laudan says

Thanks Andrea. It so happens that a few weeks ago I decided to get serious about learning some Chinese cooking and took Fuchsia Dunlop's list of ingredients to the best Chinese store in town. Trying to map her list on to what was on the store shelves was a right game. This is perfect.

Robert Jacobs says

thanks Andrea, first learned about you through that NYT article; have made the MaPo twice (with LKK) and it's been really good. Am making your Pho recipe right and will pick up one of your books. Thanks for your work!

Andrea Nguyen says

You're so welcome, Robert! Thank you for cooking mapo from the NYT story. Pho for the win this fall and winter!