Crunchy and swirly bánh lỗ tai heo are beloved by kids and adults in Vietnam. I adored them when I was young because they were charming, had a funny name that made me giggle, and were fried to slightly coconutty crunch. Viet pig ear cookies are traditionally a street vendor specialty because a vendor can specialize in it and do well. You don't an oven to make them.

You likely think pig ear cookies are oddly named but whoever named them were inspired by the slightly bent ear-like shape round shape, layered appearance evoking cartilage and skin, and the crunch that echoed the experience of eating fried pig ears. Don't worry, the recipe is vegetarian!

Where can you find pig ear cookies?

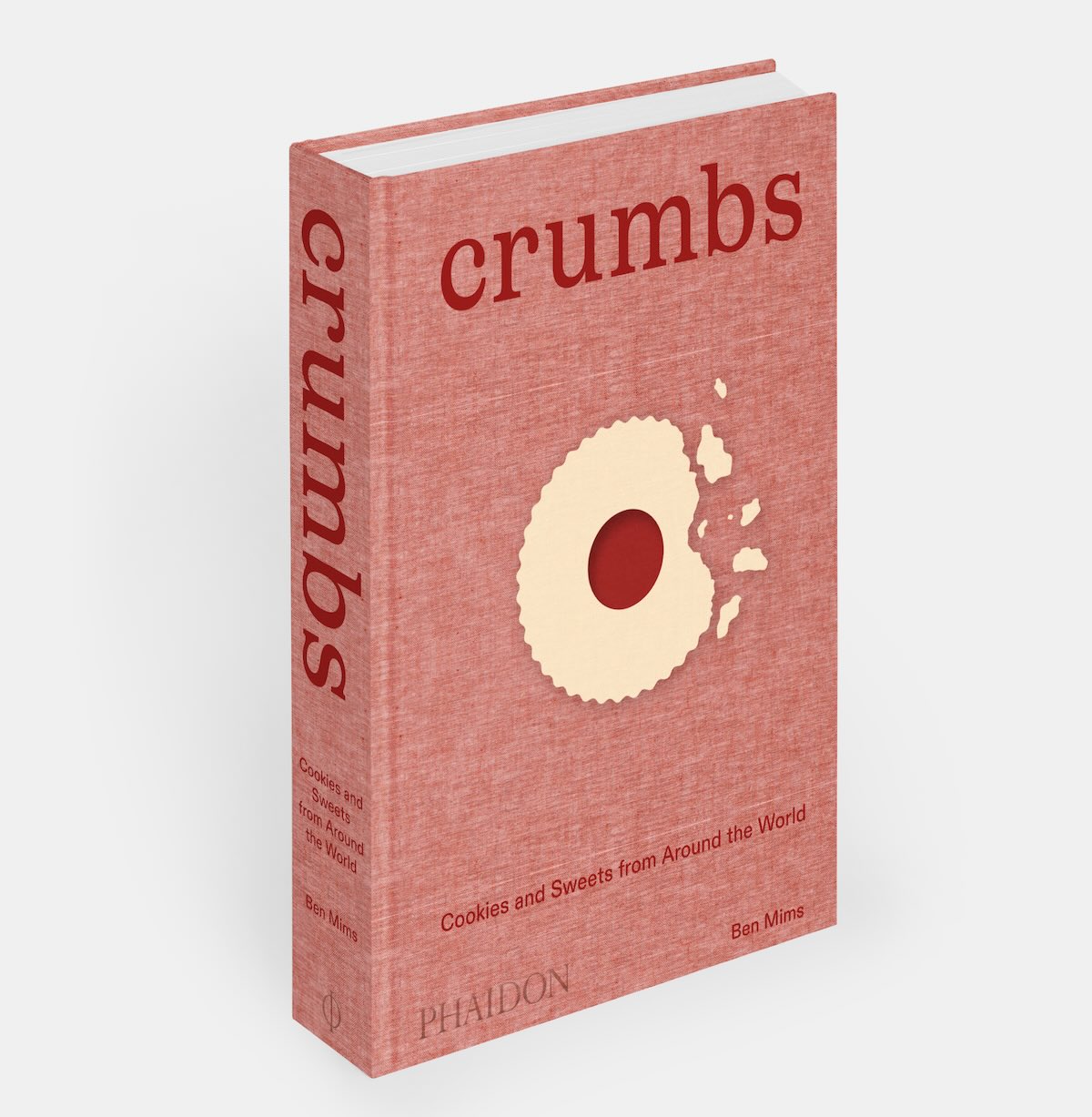

Most likely in small bags sold at Little Saigon bakeries and delis. But to be honest, I'm always slightly skeptical about their provenance (how old the oil was, for example) but with a recipe and a little oil, you can make a batch yourself. Cookie obsessed author and well-seasoned food editor Ben Mims recently included a solid pig ear cookie recipe in his book, Crumbs. Vietnamese cookies got two spots among the 300 recipes he selected from all over the globe. It's a stellar book for anyone interested in a good cookie recipe now and then, which is all of us.

There's much to learn about cookies, cooking, and culture in Ben's book, Crumbs. I reached out with some questions about cookies in Asia. Ben graciously answered, despite having cold-like allergy symptoms! What we do for cookies and cookbooks, right?

How did cookie culture develop in Asia?

AN: You mentions near the beginning of the book that Persia is the “birthplace” of cookies. How did migration of Parsis (Persian people) impact the cookies of Asia?

BM: It's difficult to be certain about the precise movements of people around the world in history, but yes, I'd say that because Parsis settled in India, they're traditions stayed with them there," Ben answered. "The cookies of Southeast Asia have more in common with Spanish, Dutch, and French sweets owing to those countries' colonial ties than the more Persian styles. This is most evident in the fats used in the cookies. In the early cookies of Persian and India, ghee and vegetable oil predominated, whereas by the time the cookies got to Southeast Asia, it's all coconut milk fat or butter. All that having been said, the Spanish, Dutch, and French influences were themselves influenced by those first Persian cookies, so in a roundabout way, they do tie back to the cookies of Southeast Asia as well.

Is there anything unique about Southeast Asian cookies?

AN: Is that why you have a separate chapter for East and Southeast Asia and Oceania? How did you select recipes for that chapter? (Above are Thai kanom kleeb lamduan shortbread cookies and Lao thong muan rolled wafer cookies.)

BM: Yes, the style of cookies for Southeast Asia is, on the whole, different from that of the Persian/Indian cookies that start out the book. Many cookies from Southeast and East Asia are influenced or come from European styles, so the cookies I chose for that region had to have a unique style, ingredient, or flavor to include it in the book. Many of the cookies from this chapter use tapioca or cassava or coconut milk instead of all-purpose flour and butter. These swaps make them unique and show how the cookies arrived one way but then adapted to native starches, sugars, and ingredients to become unique to the region.

How can cookies connect humanity?

AN: As you did your extensive research, what surprised you, if anything?

BM: The most surprising thing I uncovered while doing my research for the book really was how all the cookies of the world are so connected. Yes, they use different ingredients and flavors and forms throughout the world, but there's only so much you can do with flour, fat, and sugar, so to see all these various forms proliferate, but ultimately show how similar the cookies are to each other across the globe, was really fascinating. Every detail of a cookie has a reason for existing and once I realized that, it made uncovering all the mini histories of each cookie all the more exciting.

Below is Ben's pig ear cookie recipe from Crumbs. Make a batch or two of bánh lỗ tai heo and make a Vietnamese (or non-Viet person) very happy.

Swirled “Pig’s Ears” Cookies | Bánh Lỗ Tai Heo

Ingredients

- 2 tablespoons (30g) unsalted butter, softened

- 2 tablespoons white US granulated (UK caster) sugar

- 1 teaspoon fresh lemon juice

- ½ teaspoon fine sea salt

- 2 egg yolks

- ⅓ cup (2 ½ fl oz/80 ml) canned unsweetened full-fat coconut milk

- ⅔ cup (95g) plus ½ cup (70g) all-purpose (plain) flour

- 2 tablespoons natural cocoa powder

- Vegetable oil for shallow-frying

Instructions

- Make the two doughs: In a medium bowl, combine the butter, sugar, lemon juice, and salt and stir with a small wooden spoon or silicone spatula until smooth and creamy, about 1 minute. Beat in the egg yolks, one at a time, until smooth. Stir in the coconut milk until smooth. Scrape all the batter to the bottom of the bowl, then eyeball half of it and spoon this amount into another medium bowl.

- Add the ⅔ cup (95 g) flour to one bowl and stir until it forms a dough and there are no dry patches of flour remaining. Add the remaining ½ cup (70 g) flour and the cocoa powder to the second bowl and stir until it forms a dough. Shape each dough into a disc, wrap in plastic wrap (cling film), and refrigerate for 1 hour.

- Form the dough roll: Working on a lightly floured work surface, roll out the plain dough with a rolling pin into a rough rectangle ¼ inch (6 mm) thick. Roll the chocolate dough in the same manner. Brush the plain dough with water and place the chocolate dough on top of it. Gently roll the rolling pin over the stacked doughs to press them together. Starting from one long side of the stacked dough, roll them up together as you would a jelly roll (Swiss roll). Wrap the log of dough in plastic wrap (cling film) and place in the freezer for 30 minutes.

- Fry time: Meanwhile, line a large baking sheet with paper towels. Place a wire rack nearby. Pour enough oil into a large skillet to come ½ inch (13 mm) up the side of the pan.

- When ready to cook, unwrap the dough and trim one end so it’s even. Submerge a trimmed piece of dough in the oil in the skillet. Place the skillet over medium-high heat and heat until the dough piece floats to the surface and begins frying. If using a deep-fry thermometer, the temperature should read 350°F (177°C).

- Using a sharp, thin-bladed knife, cut off about 6 slices of dough ⅛ inch (3 mm) thick. Wrap the rest of the log and keep it cold in the refrigerator while you fry the first cookies. Remove the test piece of dough, then immediately slide the 6 slices of dough into the oil and fry, flipping once, until golden brown and slightly curled, 1–2 minutes.

- Using a slotted spoon or tongs, lift the cookies from the oil and transfer them to the paper towels to drain. As the cookies dry, move them to a wire rack. Repeat frying the remaining cookies, working 6 at a time and maintaining the temperature of the oil as evenly as possible. Let the cookies cool completely—they will firm up when cooled.

OGGardenDreamer says

Is there a secret method or special technique that can be used to encourage vertical growth of ginseng roots instead of lateral growth, maximizing the plant's potential for medicinal and culinary use?

Andrea Nguyen says

I do not know the answer to your question. This is a post about cookies.

Sandrapaish says

How does traditional Vietnamese chicken pho contribute to overall health and beauty? Can the herbs and spices used in this old school recipe provide any surprising skin benefits or promote healthy digestion?

Andrea Nguyen says

All the ginger is bound to help you. Mint is good for digestion too! I'm not expert on skin benefits but I do know that chicken pho is practically a tonic. There are several recipes on this site.